Doc Edge 2025 Craccum Coverage | The Promise

Colonised, abandoned, and silenced, The Promise shatters the myth of progress and exposes the price of forgotten liberation struggles.

Out of all the films I've seen throughout Doc Edge so far, The Promise is the only film that I feel elicits the least amount of critical input on its filmic structure and motivations than what can't already be observed once one decides to watch a film so politically justified in its borderline mechanical efficiency in elucidating its journalistic urgency towards anti-imperialism and indigenous solidarity.

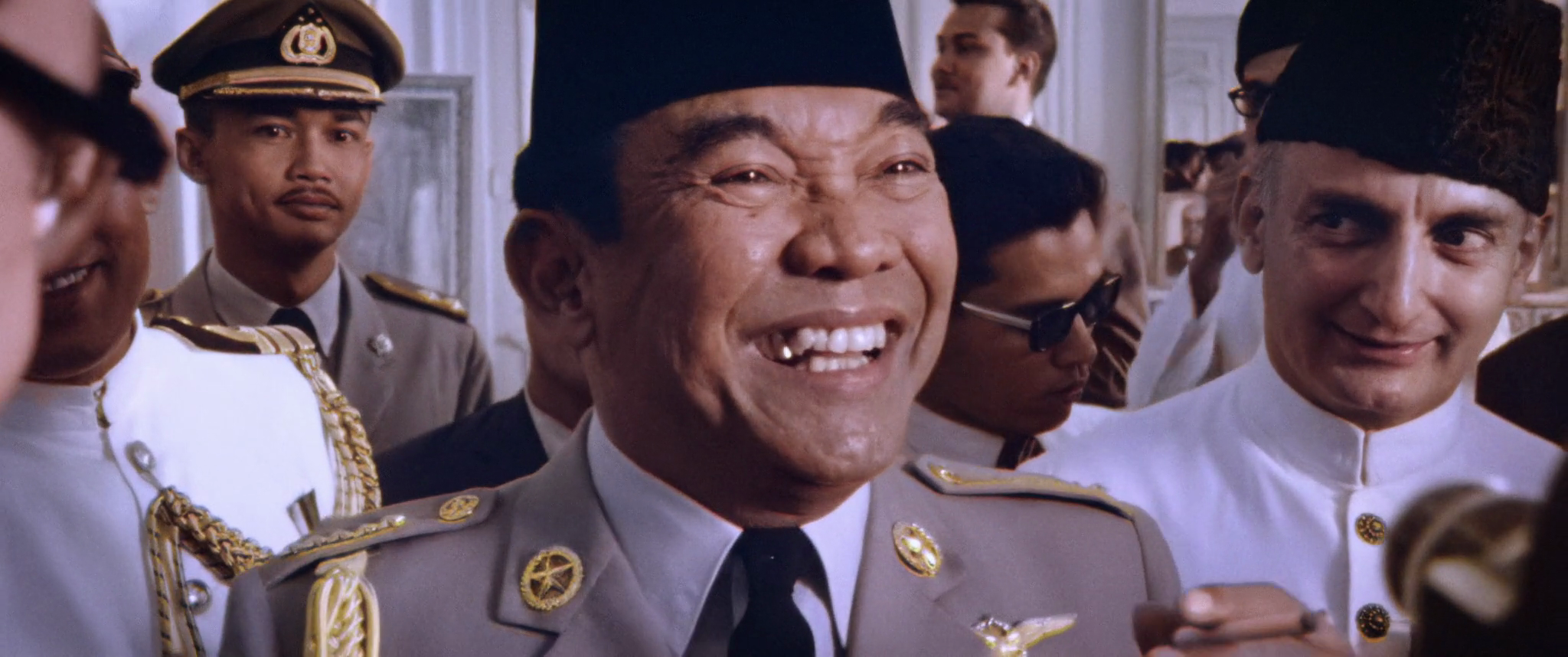

The historical struggle for West Papua sovereignty and freedom and its shockingly minimal coverage within the popular conscience of our hyper-connected, 24/7 news cycle digital landscape is an injustice The Promise seeks to rectify. The film title itself refers to the initial plans of the Kingdom of the Netherlands to secede from West Papua and aid the establishment of their own sovereign state in 1961, which eventually never came to be as the Netherlands diplomatically deserted them after the 1962 New York Agreement, leaving the West Papua region vulnerable to the neighbouring Indonesia ruled under the Sukarno-led authoritarian regime. Suffice to say, a conflict this underrepresented and diffuse in media representation leaves an uncomfortably large amount of space within the discourse surrounding West Papua that invites onlookers and neophytes to this indigenous struggle to fill it with unsubstantiated conclusions and criticisms towards the West Papua people—alongside its significant diasporic presence in the Netherlands—for their pesky complaining or lack of a widespread presence misconstrued as paltry insurgents supporting a fringe idea of a failed unified people.

That ignorant conclusion would have to satisfy two questions to be true. First, where does this West Papua identity come from if it doesn't exist? Did it exist during the Dutch occupation of the region during the early 19th-20th century? Did it exist during the annexation and massacring of approximately 800,000 thousand West Papua residents by the Indonesian government during the subsequent 40+ years since its handover from the Netherlands? Naturally, West Papuans are given a choice, if one would even call it such: assimilate to the Dutch or assimilate to the Indonesians? Of course, the irony is there was no such choice other than forceful integration and prolonged marginalisation. West Papuans have had no form of recognition in the political spheres and conventions throughout the dual occupations of the past century, if not have seen their existence relegated as an invisible 'other' of which their settlers can conveniently lay blame and graft deficit frameworks in comparison to the seeming superiority and 'civilised' sophistication of their colonisers.

Images courtesy of Witfilm.

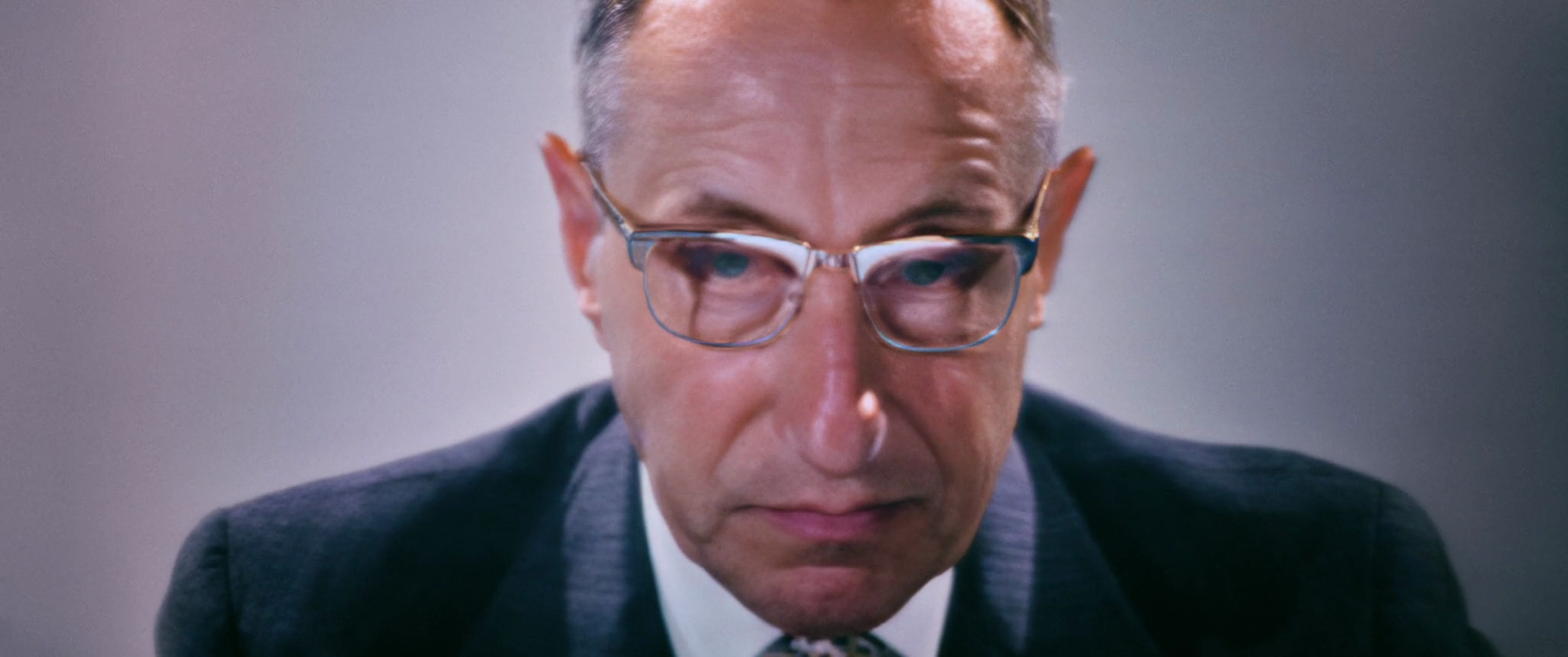

The second question is why there is barely any mention of this issue if one is just hearing it for the first time. You don't have to look that far into any literature that hasn't exhaustively pointed out the rampant American influence across mainstream news outlets and foreign policy—the latter being the dealbreaker for the Netherlands' decision to no longer support West Papua's transition into a self-determining country since it interfered with the United States' plan to make the then neutral Indonesia its ally and deter Soviet influence spreading across the rest of Southeast Asia. To quote from a 1995 United States Department of State summary:

In the Department of State, the Bureau of European Affairs was sympathetic to the Dutch view that annexation by Indonesia would simply trade white for brown colonialism, and wanted to put Indonesia on notice that the United States would not accept force as a solution to the dispute… The underlying reason that the Kennedy administration pressed the Netherlands to accept this agreement was that it believed that Cold War considerations of preventing Indonesia from going Communist overrode the Dutch case.

Less obvious—but even more enervating—is the convincing argument for the supposed economic incentives in transferring ownership of the West Papua region over to Indonesia. After geologists had discovered a remote gold and copper deposit deep into the West Papua mountains—which is now commonly known as the Grasberg mine, one of the largest gold mines in the world, the Dutch State funded multiple mining companies granting them licences to explore and extract the region for any precious minerals. What raises suspicion is these activities coincided alongside the New York Agreement, hoping to establish mining infrastructure under the auspices of American support and economic development of Indonesia and operated under an American mining company, Freeport.

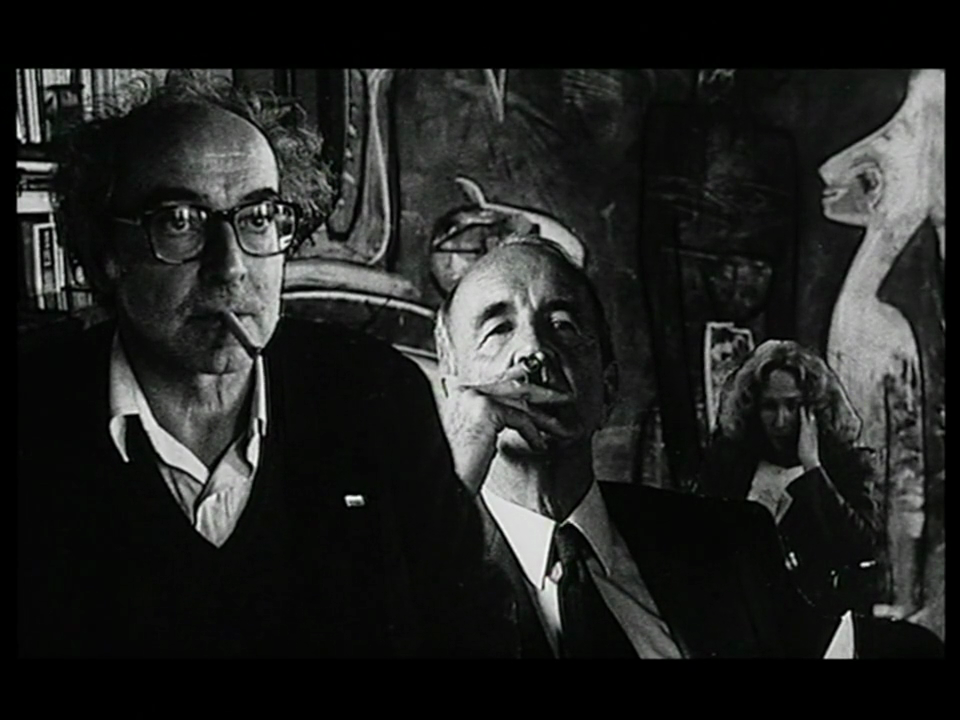

In 1991, the human rights organisation Amnesty International commissioned 30 French filmmakers to produce a short film that pleads for the release of political prisoners and advocates for their right to free speech; the short films were compiled into one feature-length titled Against Oblivion. Among the directors, which included Chantal Akerman, Costa-Gavras, Claire Denis, and Alain Renais, the filmmaker duo Jean-Luc Godard & Anne-Marie Miéville were assigned to make a film about Thom Wainggai, a West Papuan arrested in 1988 for promoting West Papuan and Melanesian solidarity and for condemning the Indonesian government's human rights violations towards his people. Godard and Miéville heavily utilise the cross-cutting technique to its Kuleshovian limits within their three-minute-long entry. Close-ups of West Papua adults and children cut in quick succession to close-ups of André Rousselet, the founder of the French television channel Canal+, who plays as himself going over a letter he has written and personally signed asking for the release of Thom Wanggai before it is mailed to then Indonesian President, Suharto. Godard was no stranger to politically subversive filmmaking, especially with the films he collaborated with Miéville from the 70s until his death in 2022. In Against Oblivion specifically, Godard & Miéville cinematically beat Rousselet's on-screen presence into submission by forcing him—a figure representing the establishment of French media—to come face-to-face with the visages of the West Papua people one after another, his gaze into the camera against their gaze into the camera.

A similar effect occurs in what director Daan Veldhuizen attempts in The Promise. We see close-ups of the multiple West Papuans he's interviewed for the film as he frequently juxtaposes them with digitally restored and colourised archival footage of the Dutch occupation of the region. The restored footage's uncanny smoothness and clarity elicit a certain dissonance and confusion; one can almost easily mistake this old footage as either filmed behind a green screen or as professional high-budget period recreations lacking the pixelated noise and low-contrast colouration characteristic of modern digital cameras. The formal conceit is clear; the historical struggle for West Papua independence has not yet dissipated into monochrome antiquity but is only brought in sharp relief and contemporaneous relevance so long as there are West Papuans in front of and behind the camera, looking directly at you and implicating you, the viewer, for their existence.

Images courtesy of Witfilm.

The Promise doesn't beg for sympathy nor sensationalise its subject; it asserts, with unwavering conviction, that West Papua's fight for sovereignty is neither obsolete nor abstract. It is a living, breathing resistance against the compounded betrayals of colonialism and global indifference. There is no closure, but instead a call—to unlearn the narratives we've been fed, to acknowledge the silence we've participated in, and to recognise that justice for West Papua is not a matter of history but of urgent, unfinished business.

The Promise Trailer │ Doc Edge Festival 2025

Doc Edge Festival is in Auckland from 25 June through to 13 July. The festival will also be showing in Christchurch and Wellington (16 July - 27 July).

The Promise will be premiering in Auckland on the following dates:

1 July 2025 - 8:15pm - Bridgeway Cinema

6 July 2025 - 5:00pm - The Capitol Cinema