Film Review: The Watermelon Woman

While this film's title is a play on the 1970 movie Watermelon Man, Cheryl Dunye's The Watermelon Woman does not play around its traversal of memory, race, gender and sexuality.

The Watermelon Woman ends with an epigraph that reads, “Sometimes you have to create your own history.” This encapsulates the film so perfectly in such few words that even a full review article might not do it justice. Still, an attempt must be made to bring it to those who have not yet heard of it.

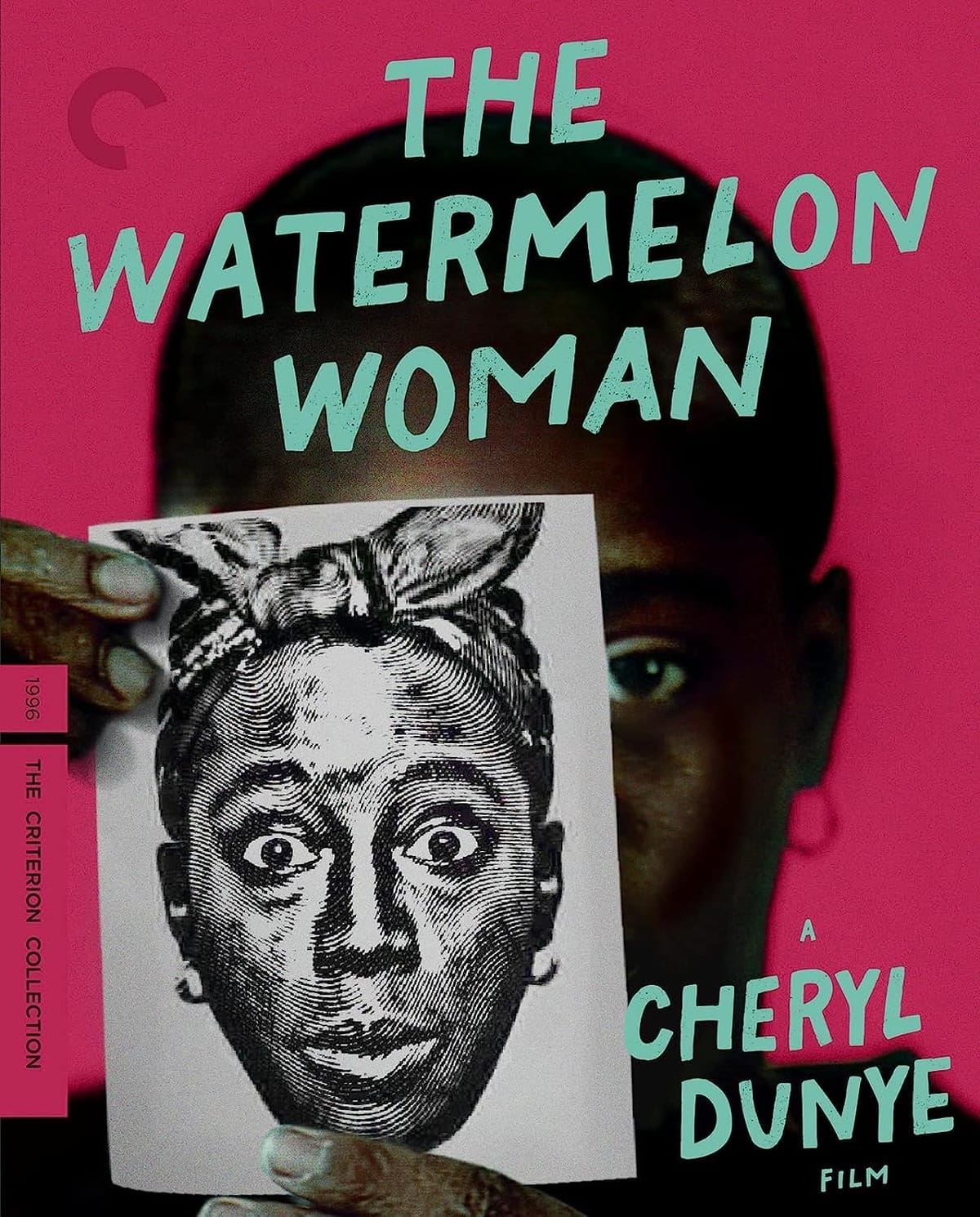

Directed by Cheryl Dunye, The Watermelon Woman was released in 1996 (1997 in theatres) and was the first feature film at the time to have been directed by a Black lesbian, on a Black lesbian. It won the Teddy award at the Berlin International Film Festival upon its release, and an Audience Award for Outstanding Narrative Feature at Los Angeles' Outfest. It is experimental, delightful, and its treatment of its themes is subtle and effortless — one can fully understand why this film is considered by many to be an invaluable classic in the history of filmmaking. The film is a mix of documentary and narration, with segments from Cheryl’s life and the film she is making, complete with ‘archival’ footage, dated photographs and classic films. The 86 minutes of The Watermelon Woman feel like the work of a lifetime and a 15-minute chat with a close friend at the same time — specifically that one friend whose rich life experiences make us wonder how much we have taken for granted.

The plot follows Cheryl, played by the director herself, on her journey to make a film about the titular Watermelon Woman, an actress who played mammy roles in movies during the 30s. The Watermelon Woman is played by Lisa Marie Bronson, and seen primarily in photographs or film material throughout. Alongside her friend and coworker Tamara (Valarie Walker), Cheryl sets out to uncover the history of this actress and to document her life, though this proves quite difficult when she was not even credited properly! A central theme of the film is the opacity of the archival history of Black actresses, and Cheryl runs into several roadblocks during her research — she asks a myriad of people about The Watermelon Woman, she consults books, she consults references, she does everything she can think of. It is only when she asks an older Black lesbian who knew The Watermelon Woman personally that Cheryl finally discovers her real name, Fae Richards. She also discovers that Fae Richards had been in a relationship with Martha Page (Alexandra Juhasz), the white female filmmaker whose films she played minor roles in. In the end, even knowing her name is not enough in a world where Black women, and Black lesbians in particular, are constantly rendered nameless and erased.

Suppressing information about Fae Richards is not something that happened in the past and is left in the past, because even in the present her legacy seems to be actively prevented from being brought to the broader public. Page’s family vehemently denies any relationship between Fae and her, and it turns out that Page herself likely mistreated Fae too. Even when Cheryl and her other coworker Annie (Shelley Olivier) go all the way to New York to look through an archive of lesbian history, they are prevented from documenting it by a white lesbian. The particular intersection of race and sexuality means that the historical experiences of Black queer women are gatekept from themselves, and their agency is made secondary to whiteness even in a queer space. As the plot progresses, we start to see parallels between Cheryl and The Watermelon Woman herself: in Cheryl’s new relationship with Diana (Guinevere Turner), a white lesbian, and in the obstacles she faces being Black in the filmmaking industry. This is echoed by a scene in the film where Cheryl is shown mimicking a segment played by Fae Richards, not taking herself seriously, and yet seeing herself in a disremembered Black lesbian from the past.

One of my favourite scenes is when Fae Richards, in a movie being played on the television, appears as the dark-skinned sister of a light-skinned woman. The woman is attempting to pass as white, putting powder on her face, and asking, “Why can’t I choose to live in this world?” In the scene, Fae slaps her. The broader context here makes it very interesting — it replays when Cheryl is getting together with her white girlfriend — but even on its own it is a poignant scene highlighting the danger of proximity to whiteness. While it can be a way of seeking upward mobility, it also centers whiteness from start to finish, and this very topic comes up in conversations between Cheryl and Tamara. It is also reflective of the relationship between Fae and Page, through whom Fae accessed Hollywood but who simultaneously prevented her from becoming a star.

Despite The Watermelon Woman being released almost thirty years ago, it speaks to issues that are still timely and humour that — I imagine — hits much the same. During an incredibly awkward dinner, Cheryl trips over her words, and this goes entirely unaddressed and unedited. This happens at another point with Tamara as well, and while these are all natural things people go through, the film context does make them somewhat funny. Camille Paglia, playing herself, has a satirical scene parodying a white feminist film critic which is also quite humorous. She rambles nonsensically about her Italian heritage justifying her racist views towards Black iconography and history, saying there was no reason for watermelons to be viewed negatively when they had the Italian flag colours (for those unfamiliar: watermelons were used as a racist trope to portray Black people as ‘simple minded’ or ‘unclean’ — the Italian flag has nothing to do with anything here). Another scene that is treated lightly, and almost with a sort of mirthful disbelief despite being quite harrowing, is when Cheryl gets arrested for apparently looking like a meth addict, and accused of having stolen her own camera. There is no elaboration on this, but isn’t that the sort of racism Black people experience all the time? She is also called a man for not conforming to cisheteronormative standards of femininity. Just a look at her life as a Black lesbian — which, as Cheryl shows us, can only be documented by others like her. In the changing city of Philadelphia, whiteness interrupts and polices Black and queer bodies, with Black lesbianism being uniquely at risk.

To end, I will not spoil you on what the epigraph refers to so the element of surprise I felt can hopefully be passed on (though you may have a good idea already). To quote Cheryl when she is talking about what kind of film she wants to make, “I know it has to be about Black women, because our stories have never been told.”

The Watermelon Woman raises questions about the processes of tokenizing and erasing Blackness, about who decides what is to be remembered and what is to be discarded, and what the barriers between Black queer people and their own history are. The cast of Dunye’s personal lens shows us all of this and more, and answers the question: what do you do when your own history is unreachable to you?