Girl From East Asian.

A personal reflection on navigating the weight of Confucian traditions and the longing for liberation.

Between Tradition and Freedom: An East Asian Girl's Voice

I want to talk today about the stories of us East Asian women, and I want to start from my most original perspective.

From my upbringing, to the realizations I gained after engaging with Western culture.

As an East Asian woman, I have never thought this was something to be celebrated. My society is filled with the grand narrative of Confucian thought; I understand Confucian values of respect for hierarchy, humility, tolerance, and harmony.

But I cannot truly allow my free-spirited soul to be confined in a narrative of male superiority where women are constantly forgotten.

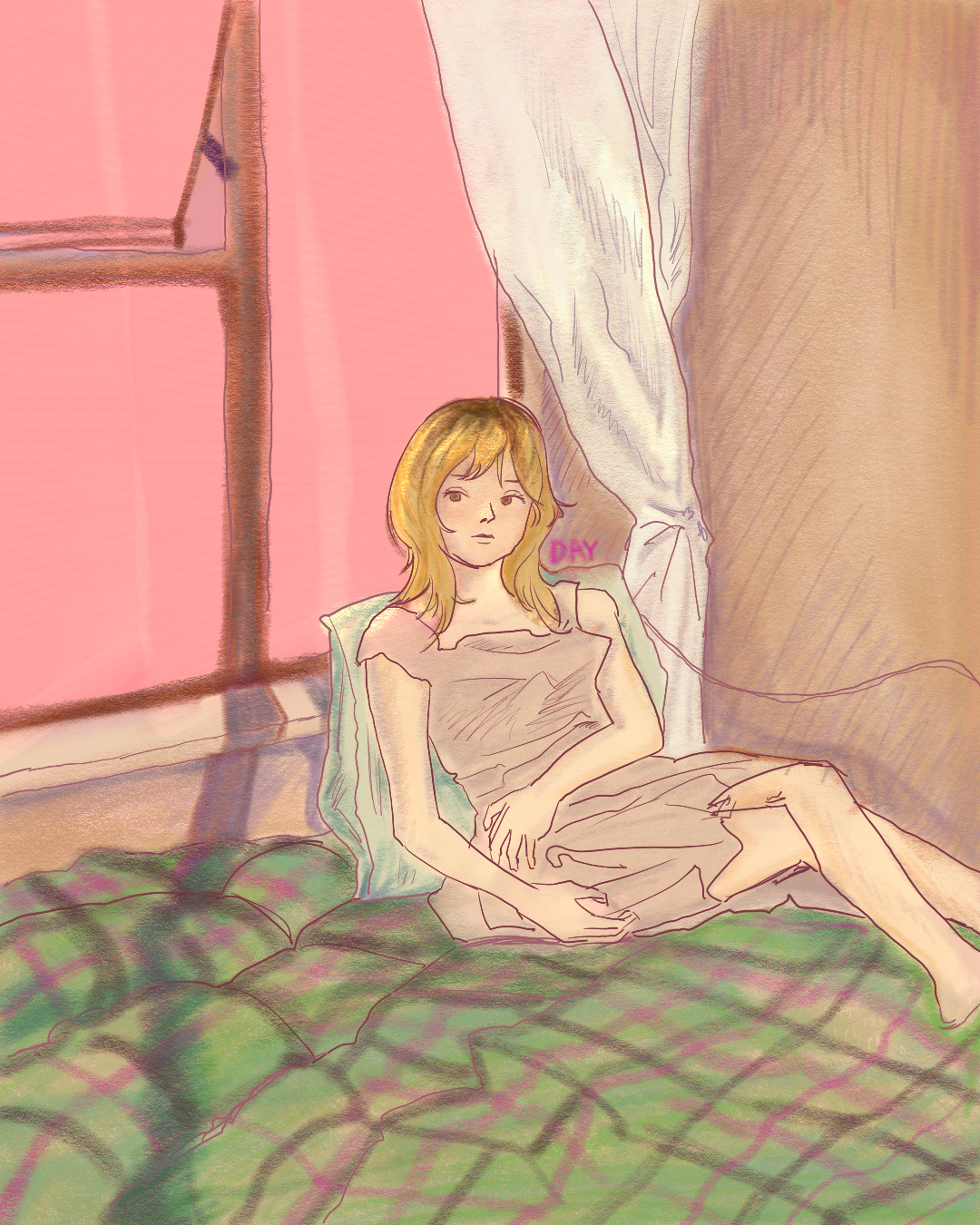

So I talk to the stars in the sky, fall asleep on lush green grass, and shed tears at the moment a plane touches down.

Yet I have never been able to find what contribution I could make for women. This grand narrative contains so many intricate details that every time I criticize Confucian thought, I am told I am blindly worshiping the West and forgetting my roots.

As a child, I often heard these words: girls should be reserved, sensible, not too assertive, but gentle and weak. We even have a deeply gender-restrictive saying: “For a woman, lack of talent is a virtue.” It means that a woman should not know anything, should not study, and should not learn any skills—this is considered an attractive quality.

I have constantly thought about what value East Asian women are truly given.

I have seen women who cannot be financially independent, who dedicate their whole lives to their family and children, only to be repaid with their husbands’ infidelity, domestic violence, and neglect from their children. I have seen East Asian housewives who work tirelessly every day, only for their husbands to take them for granted. I have seen a society that treats being a housewife as an unquestioned expectation for women. Of course, I have also seen terrible mothers-in-law who demand that their daughters-in-law give birth to a son so that the family line can continue. In the classic East Asian narrative, a woman’s only purpose is to bear children for the family. I have even seen traditional family systems in which only men inherit the family business, while women maintain the family’s image through arranged marriages. I have seen the women of my grandmother’s generation deprived of education, because society believed women did not need to learn.

I have also seen how such a system prevents many East Asian men from knowing how to express love to a woman. They do not know how to show their emotions, and I think they themselves do not see this as a problem. In my society, you will see men who clearly love their wives but do not know how to express genuine feelings. Some men even lack the basic respect for women, believing that working hard outside the home is proof enough of their love for the family.

But our society never considers this a serious problem.

Life still goes on—people rise at sunrise and sleep at sunset.

Yet the cries of East Asian women are continually eroded by this old system, drowned in fear.

We are neither like white women, who have fought with all their strength for women’s autonomy for centuries, nor are we naive girls who know nothing. And so I find myself caught between two layers of clouds, raining down lonely days.

These women struggle, yet remain neither servile nor loud. They cry, yet try to wipe away their tears. They work tirelessly, yet still believe it is their mission assigned by society.

Sometimes, I am grateful to be born in this era, though it is deeply unfair to my position. But at least, as Wollstonecraft said, I have learned reason, and I have received an education.

So I keep learning to read the unfairness of the system, to understand how it devours women’s ideals, but I still struggle.

I study reason, I study politics, I study history, I study patriarchy, I study feminism, I study Confucian thought, and I even study the melodies of Western freedom.

But in the end, I realized not all women have this opportunity. And so they remain bound by chains.

People say sex workers engage in vulgar work, yet no one condemns male escorts for doing the same.

The system, class, and gender all force some women into an endless pull between morality and reality.

The system subjects them to unequal treatment. Class deprives them of the right to access quality education. Gender traps them in certain occupations and moral struggles.

Some take on such work to feed their families. Others are forced into it after being violated at a young age.

So I ask East Asian society: what right do you have to judge someone’s gender? Is it simply because she is a woman that she deserves to be humiliated?

We have never participated in their lives—so what right do we have to say what they do is wrong?

Let me be clear: I do not support the sex industry, but I believe bodily autonomy is an important consideration. What I emphasize here is that we are not them, and therefore we have no right to insult or dictate their lives.

So I often think at night—after learning all these theories and knowledge, I am still like a lost girl living inside the old system, unable to help them, and unable to help myself.

So I count the stars in the dark and drift to sleep, because only the stars will not criticize my daydreams.

Breathing, feeling my heartbeat, the slight haze in my eyes in the morning. I always tell myself I am lucky, but I am also always sad.

Because I know I am both traditional and yearning for the new era. Like a girl born inside a grand East Asian narrative, longing every day to break through the framework of the old system. And so I keep Westernizing myself, trying to absorb the essence of Western women’s liberation, yet I can never fully share this essence with women of the same background as me.

So I keep waltzing to the tune of Western freedom, sketching the effortless grace of French women, breathing in the century-old books of an English library.

But I have always known—I am still an East Asian woman. Like my mornings, when I still stand in front of my closet wondering if I am dressed too revealingly and might disturb others. I still fear interacting with East Asian men. I am still like a torn two-faced figure, pretending to be gentle, polite, emotionless, and calm before others—while my heart is like a raging tsunami, filled with deep accusations and curses against all inequality.

So, as I said, I am still that girl sitting in a café, watching the ebb and flow of conversations, yet still envying the woman in stockings singing and dancing at the bar at night.

So I continue—contradictory, twisted, yet calm, yet wild.

And I think this is the eternal trouble of East Asian girls.

If one day I could soar as freely as a flock of birds in the blue sky, I would want to fly to the edge of the universe.

Perhaps there is where I truly belong— No etiquette, no order, no male superiority, no “men on the left, women on the right,” no “men outside, women inside.”

I would simply be myself. And what I mean by being myself is this: Wearing what I want without being subject to the male gaze. Daydreaming alone without being laughed at. Defending my stance without being met with contemptuous stares.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in Craccum are those of individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial team or the publication as a whole. While we aim to ensure accuracy and fairness, Craccum cannot guarantee the complete reliability of all information presented and assumes no liability for errors or omissions.