Interview with Fania Kapao: Whau Local Board Candidate & UOA Student

Fania sat down with Craccum and opened up about her political journey, what keeps her motivated and explained how students can get more involved in New Zealand politics.

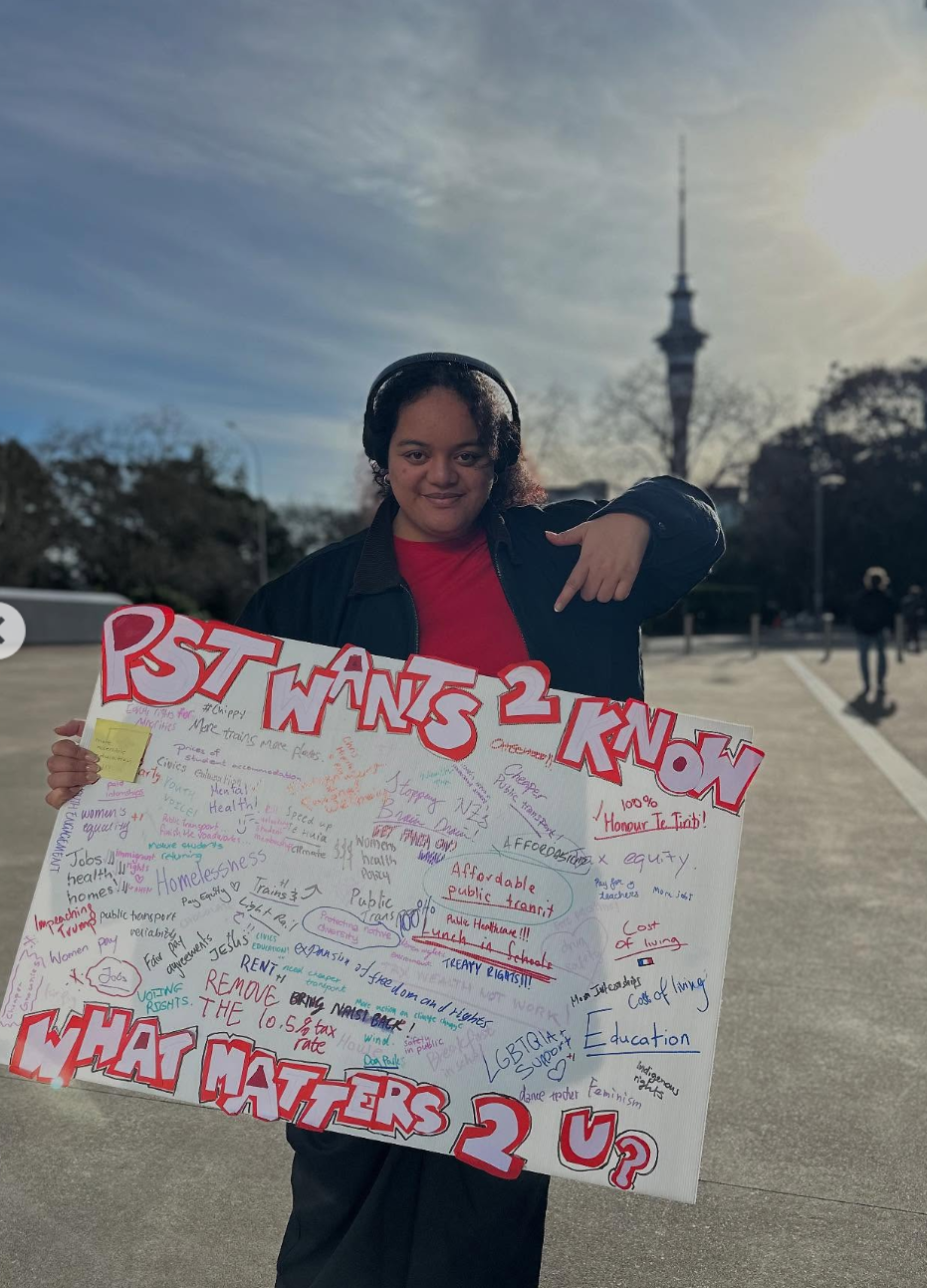

Fania Kapao (@faniakapao) is a young rising star in the world of Labour politics and a postgraduate student here at UOA, who is also serving as this year’s AUSA Postgraduate Education Vice-President and is a regular Craccum contributor. You may have seen some of her work in Organising the AUSA Fair Pay protest earlier this year, she also debated at this year's Baby Back Benchers. At the moment, she is also running for the Whau Ward Local Board. Fania is very humble and shy by nature and very reluctantly agreed to speak to Craccum about herself.

Local Body Elections close Saturday 11 October 2025.

What songs or artists have been on repeat for you lately? What do they say about your mindset right now?

[Opens app]. Lots of Troy Kingi (just exposed myself [laughs]). Like, almost every second song is Troy Kingi. Lots of Troy Kingi and Che Fu. This is like… wow.

A lot of these songs I’ve had on repeat—Misty Frequencies, All Your Ships Have Sailed—really speak to my childhood and journey. They’re deep songs for me; they mean a lot.

Misty Frequencies, for example, speaks to how everyone has their thing, their niche. Sometimes your background isn’t the best—like your origin story isn’t super flash or whatever—but people still have dreams and things they’re naturally drawn to. And sometimes, you’re the only person who believes in that. I’m pretty weird being into politics since I was six.

With All Your Ships Have Sailed, Troy Kingi talks about having to be his own father, and now he’s got his own kids. He’s chasing the idea of what it means to be a good parent and role model, and how hard that is when you don’t have that blueprint yourself. I really resonate with that. My life hasn’t been the easiest—lots of my peers take for granted things I never had. Trying to give those things to myself as an adult is hard when you don’t know what is and isn’t normal.

With politics, I’ve had to accept that there are aspects of me that aren’t polished or perfect—and sometimes, that’s the best part of who you are in this space.

Long ramble, but I gravitate toward songs that speak to me and help me get through the stuff I’ve been through.

What’s your go-to restaurant and what’s your order?

Mmmm, Ramen Station in New Lynn. I usually get the Station Soba with pork, but the other day I tried the Miso Tonkotsu Ramen and it was pretty good, not gonna lie.

I know this isn’t part of the question, but the other day we went to Nanny’s Eatery—exactly a year after interviewing JessB for Craccum—and it’s really good. It’s my second favourite. The vibes are on, and the flavour is immaculate.

Both of these restaurants just transport you. You’re not in Auckland anymore.

What role do you think student media, like Craccum, plays in political awareness and accountability?

I think it plays the biggest role in student politics, especially. I don’t know why this is even a question—it should be common sense. People need good journalism and independent media that discuss all kinds of topics. Obviously, there are some we need to be careful around, but that doesn’t mean you should silence entities like Craccum or treat them like a mouthpiece for an organisation.

Like, if you’re feeding someone lines to say—like a student magazine—and claiming “this” is the student voice, you can’t say you represent the university if it’s just a couple of people who graduated eons ago. Entities like Craccum play a huge role in disseminating information on a wide scale.

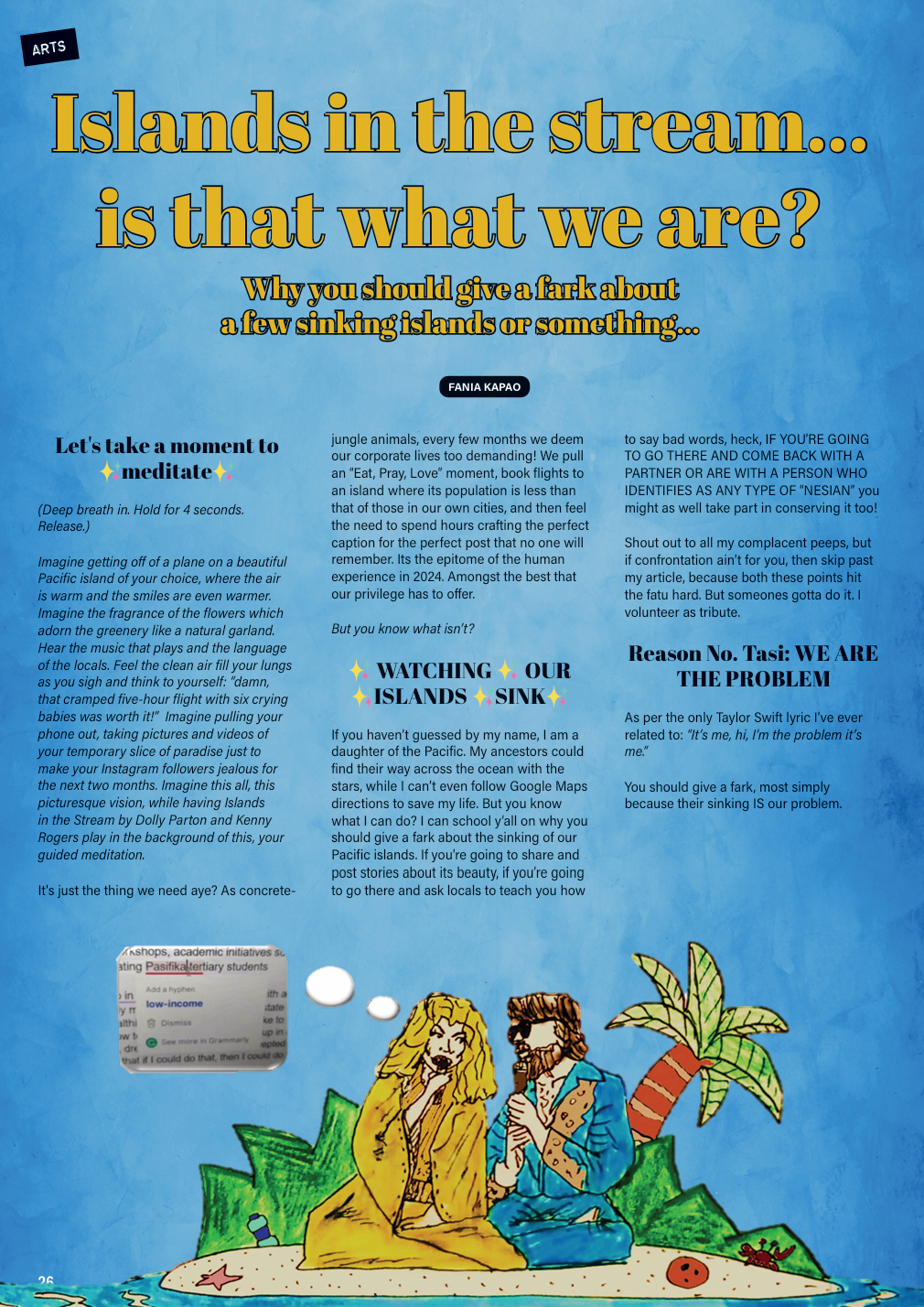

We’re seeing this shift where people are moving offline (I’m one of them), and gravitating back toward physical media. Like, Sabrina Carpenter puts out vinyl, cassettes, and CDs—not just digital. In time, that’ll spread to the media too, which is why it’s fundamental to continue and preserve print magazines in the student space.

Plus, it’s really cool to see your work in print—or your friends’ work. Hear the goss from the halls. Understand what’s happening at the university on a wider level.

I wish Craccum could keep the accountability of AUSA and other university figures. As Post Grad Education VP, I’d like to know where I could improve, or how students perceive me—because that’s the only way you get better: through criticism. As long as you’re not a dick about it, I see no harm in Craccum being that source of accountability. Why is that not the case at the moment? I have no idea.

Local politics often fly under the radar for students. Why should they care, and what real impact does it have on their daily lives?

If you asked me this question a year ago, I’d probably say “dunno” [laughs]. It’s totally understandable—it flies under the radar. Mostly older people have the time of day to care. Young people have so much going on, and life develops for them by the second. Local politics, which we haven’t been taught to understand, feels like an inconvenience—not like a civic duty.

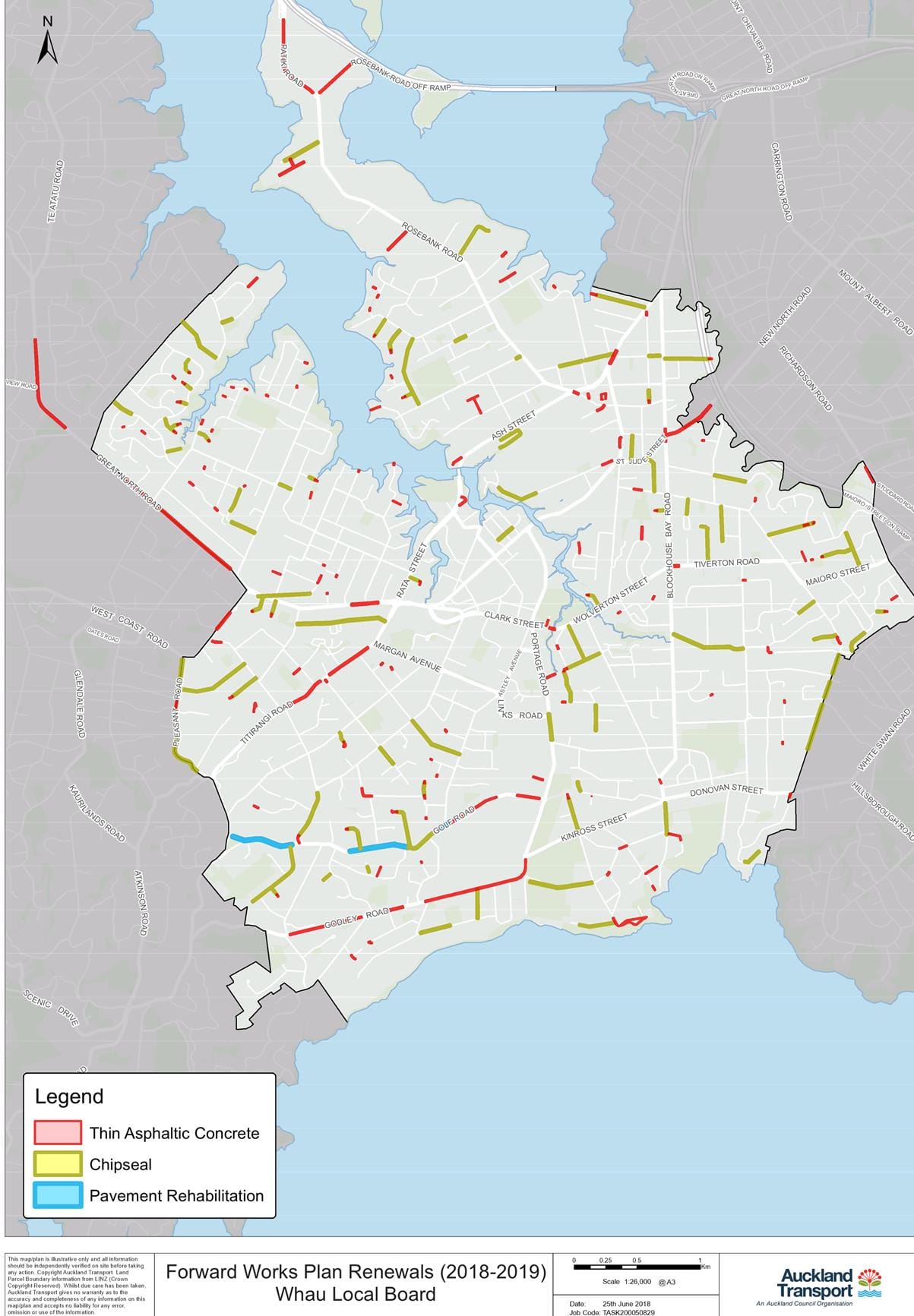

But you should care, because local boards control a lot of what you use in your everyday life. I know people mostly think of central government when it comes to how the country is run, but local boards and local government are way more connected to the utilities you use every day—green spaces, water quality, construction permissions, public transport, rubbish, pollution. All these things that people don’t really think about in their day-to-day life.

I do believe local boards should reflect the diverse demographics of their areas. Sadly, that’s not the case. Young people—under 30—are usually not represented, so a lot of decisions that go through local boards can be dismissive of young people. That’s disheartening, and it feeds into why local politics flies under the radar. Why would you care if they don’t care about you?

For example, in the Whau area, about 30% of registered voters are under 30, but currently there’s no one on that board who fits that demographic. If you expanded that to include children, it’d be even more disproportionate. And that shows in the infrastructure. A few weeks ago, I was doing door-knocking—there’s a playground for kids, and just 100 metres away, the pavement was cracked, with electrical wires hanging overhead that should be underground. To me, that speaks to why it’s necessary to have a board that’s conscious of young people—and why young people need to take more interest in it.

Many of the older people on the board have been there for years, and for them it becomes personal—it’s their identity. Like, they are the local board. But that’s not the point. The point is to ensure the communities we live in are actually livable.

Where do you stand on the Make It 16 campaign? Do you think lowering the voting age would solve low voter turnout?

That’s a hard one. Because I do believe in Make It 16, and I think young people have so much wisdom and understanding of what they want their futures to be. But at the same time, there’s a lot of work that needs to be done around Civics education in New Zealand.

Studies show that the more you teach kids about Civics, the more likely they are to vote and participate. Especially if you’re working at 16—it’s kinda rats that you don’t get a voice. But in the same vein, the onus falls on the government of the day to make sure rangatahi are properly educated—what their rights are and how they can shape the future.

There’s no point lowering the voting age and doing no follow-up work. It’s like planting seeds in a garden without tending to it.

For Make It 16 to be fruitful, there should be more focus on social sciences and helping students understand the voting system. I was never taught about it at school. I only learnt about it at uni—when they explained the different branches of government, how justice works, and how Parliament functions.

We shouldn’t have to wait until law school to find out the secrets of our government. Everyone has a right to know how it works. The government needs to back it.

The local election candidate booklets can be overwhelming. What are some practical ways students can cut through the noise and make an informed choice?

First of all, if candidates aren’t speaking your language—like social media—if they’re not connecting in a way you’re used to, don’t vote for them. Cross them out immediately. A good candidate learns to connect with different people.

I never used Facebook before three weeks ago, but I understand a large section of the voter base is on Facebook. So I feel like the world is in the palm of your hands—look them up on Instagram. Social media is a really powerful tool.

The blessing and curse of social media is that everything’s condensed. If you find them online, they’ll probably have a post with five slides you can scroll through that summarises their platform, or videos showing who they are and what they’ve done. You don’t have to strictly go by the booklet—I know I don’t. I need to understand the person as a whole.

Also, talk to people. Like your peers. I’m a bit weird—my circle is very political—and I get that’s not the case for everyone. So speak to your friends about the values you have and what you want to see in your community. What’s working for you, and what’s not? Maybe you want more artistic events, or you want to start a fitness group. Then look at which candidate shares those values.

It’s hard at local elections. It’s not as public as central government—there’s not a lot to go off. Social media and word of mouth are your best friends.

Beyond the ballot box, what are some other ways students can shape politics in New Zealand?

Increasingly, in this day and age, it’s more about who you know—not what you know. I’m not a huge fan of that, but if students can start forming good working relationships with MPs, local figures, and actually workshop changes with them, that’s a huge tool. It’s fundamental. Students can use that to shape politics.

With this current government, facts and figures aren’t the priority. So yeah—it’s not what you know, it’s who you know. Which sucks, really bad. But you don’t have to sell yourself out. Find people and leaders who share your values, who want to see you grow, and who are genuinely dedicated to improving the society we live in. In my opinion, that’s the greatest tool you have.

Social media is another powerful tool. You can spread information quickly—share, comment, screenshot. It exists to help us connect with each other, and through that, connect over our ideals and values. Young people aren’t doing what they used to—turning up in the town square and yapping. So sharing opinions online is really important, as long as they’re not harmful or rude.

A good way to shape politics is by getting involved with your youth wing, if you’re aligned with a party. Princes St Labour has a long history of producing Local Board Members, MPs, even Helen Clark. So get involved with your youth wing—it’s cool getting together with other young people, building friendships. I know it can be toxic sometimes, but in those cases, it’s about trusting your gut.

Staying up to date with the news and understanding what’s happened historically is really important. What’s worked, what hasn’t, what you could modify, what you need to avoid. Educate to liberate.

A lot of what you need as a young person to shape politics is the ability to acquire knowledge—and then leverage that across the connections you’ve made, to get your message into rooms you can’t be in yet.

You’re clearly passionate about Labour. Where did that fire start for you, and how has it evolved?

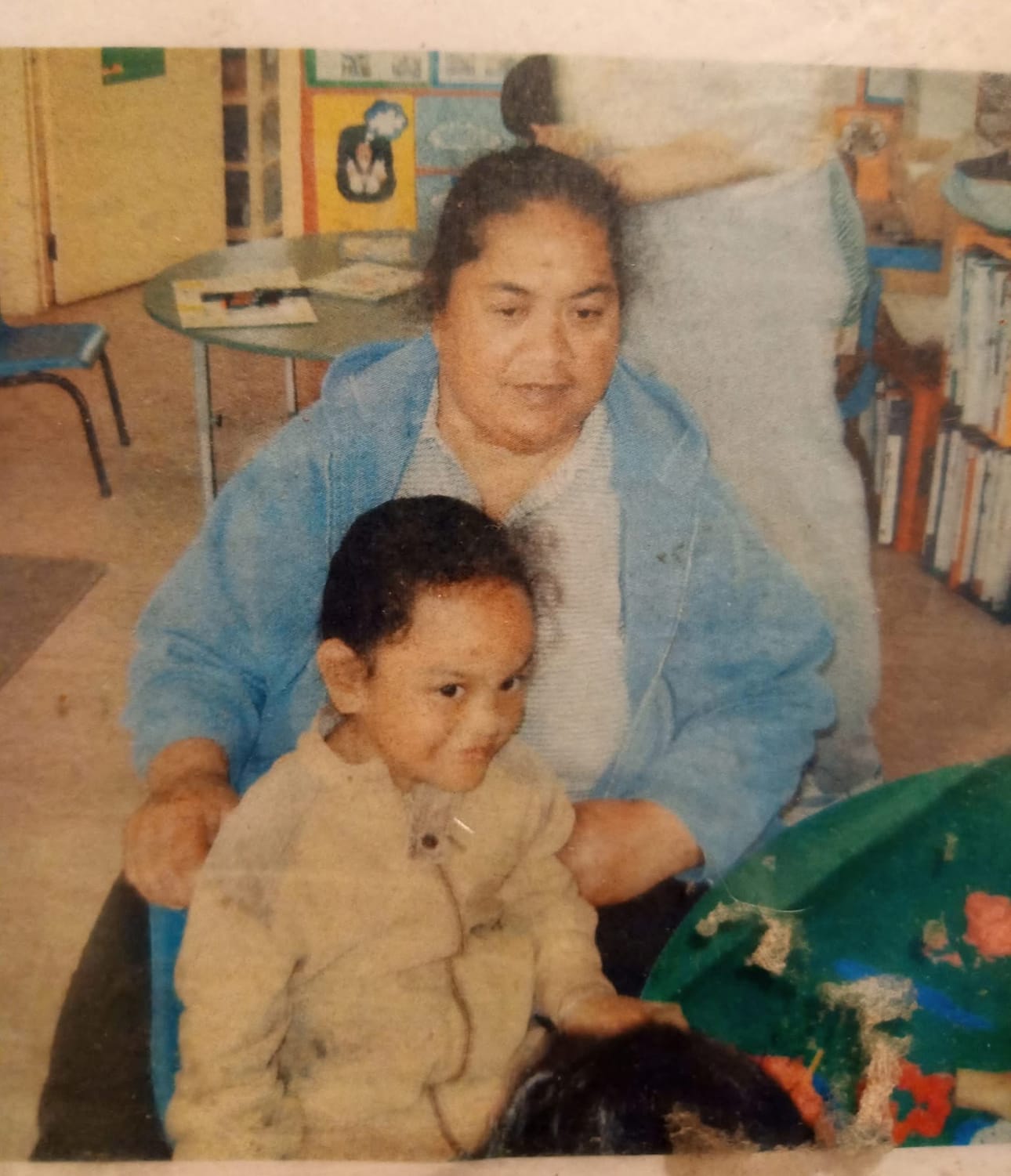

How much time do you have? [laughs] I have this really distinct memory from when I was about six. My Nana and I were in the kitchen making dinner. Earlier that day, she’d received a letter. While she was at the oven, she asked me to read it to her—it was from kindergarten.

I got stuck on one word. It took me about two hours to figure out how to mouth it. We lived in a multigenerational house—my mum, aunt, uncle, and grandad had all come back from work and school. And with all the conviction in the world, I said, “You are been evacuation.” The room went silent. Everyone looked at me confused. My aunt took the letter and read it properly—the word wasn’t “evacuation,” it was “evicted.”

I didn’t know what that meant at the time, but I felt this deafening silence fall over the room. And for my Nana, that was the first time I’d ever seen her scared. I didn’t understand any of it. My grandad and I went to watch the news. Helen Clark was on TV, walking across the tiles, and my grandad was nodding along. It had something to do with the letter I’d read. I realised that the people on TV and the decisions they made were connected to our two-bedroom state house that had housed nine people at one point.

That’s kind of where it started for me.

Later, I found a dictionary and looked up what “eviction” meant. I still didn’t understand how a government department—whose sole purpose is to look after people and house them—could be so heartless and issue eviction notices. I remember in the lead-up to that letter, my Nana and Mum were looking for help and being turned away by everyone. Spoiler: we didn’t get evicted but had to move out a few years ago.

That moment is where I pinpoint it all starting for me. Then came experiences with the healthcare system—queues of people waiting for dialysis, long waitlists. It was tough to take in as a kid. You feel so helpless. It radicalises you in a way that’s really niche, I think. For me, it exposed how terrible and selfish the world can be—and I didn’t want to be anything like that.

My love for the Labour Party stems from my grandparents. Everyone in my family has been a union delegate. My grandparents were staunch Labour supporters, so I grew up with the mindset of protecting workers’ rights. Workers drive the economy. I’m very much a socialist, and I align with the old Labour—the one that sticks up for workers, everyday people, indigenous rights, and puts people over profit. That’s become a huge phrase for me, a huge belief. It’s something the party fought for.

These days, the party gets a lot of criticism. But I genuinely believe it’s the one party that truly represents everyone—because our membership is diverse, from all walks of life. I’m passionate about the party because it’s made up of awesome people. Volunteers, support people—kind, generous, with so many different experiences. It can be your family away from your family. And that’s something I’ve really needed over the past while being on the campaign trail.

Who is Uncle Phil?

Phillip Stoner Twyford, MP for Te Atatū. There’s a lot I could say about Phil, but I credit so much of where I am now to him. I don’t think I would’ve found myself on this path if I hadn’t met him—somehow, if I hadn’t crossed paths with him.

I went to a college that wasn’t reflective of my background. The kids there were children of MPs, diplomats, business owners. I never fit in. I felt like I had this huge secret—that I was sleeping on a couch in a state house my family had lived in for 30 years, with asbestos everywhere, looking after my three younger cousins. I felt deficient, like I’d never amount to anything. I’d go with my mum to the WINZ office and see my future in the people sitting there. I wasn’t ashamed of them; I wanted more for them. I felt like the system had let them down—and would let me down too.

Youth Parliament was happening at the time. Phil sent out the application. There was one girl in our class who kind of got everything (she did work hard), and I felt like all the odds were against me. No one would care about a poor Island girl from Avondale. But I poured my heart and soul into that application. It felt like the only shot I’d get at saving myself and my family.

I was selected to go to a speech competition, which was surprising. I still felt like I was destined to lose—because the other students were just like the ones I went to school with, from well-off backgrounds. My speech was about the drug epidemic that swept through my life, harmed family members and friends I grew up with. I talked about how the system let people like me fall through the cracks without caring, and how we didn’t choose the lives we have—so we shouldn’t be punished for it. It resonated with the selection board. I won, to my own surprise.

Kapao speaking at Youth Parliament in 2019.

Phil became a mentor to me. I went to a bunch of events with him. He introduced me to MPs I was terrified to meet at the time—who I now work closely with. He told me about his work at Oxfam and international activism, which sparked my own love for activism. I owe a lot of who I am and where I am to Phil—for taking a chance on me.

I remember asking him a few years ago why he chose me—because I struggle with imposter syndrome. He said, out of everyone who applied, I had the most hunger, the most to gain, but the least resources. He said it was like finding a diamond in the rough—but the diamond doesn’t know it’s a diamond. That quote made me cringe for a long time [laughs] because I’m not great at taking praise or compliments. But looking back, I’m grateful someone saw something in me and believed in it enough to give me a chance at something so prestigious.

I don’t know where I’d be if that hadn’t happened—and honestly, I don’t think I want to know [laughs]. Uncle Phil is like family to me. He means a lot. And I hope everyone finds their own “Uncle Phil”—someone who believes in them so deeply, even when they don’t believe in themselves.

What’s the biggest misconception people have about young politicians, and how do you push back against that?

[Sighs] They were all pretentious, stuck-up bastards [laughs]. Or that they’re all privileged kids of Pakeha background or whatever…I’ll say—in some spaces, that’s true. So it’s not a full-on misconception. But I don’t particularly see myself that way, I don’t even see myself as any sort of politician. I don’t know—is that arrogant? [laughs] To me, I’m just a nerdy Kuki/Hamo girl from the 828 with a really bad tendency to overthink everything lol.

Personally, I come from very humble beginnings, and I feel like the story of my life—the hardships, the shit I’ve been through—helps me push back against that narrative. I love what I do because of the connections. I used to mentor rangatahi who were deemed “at risk” by the system. But when you talk to them, they’re not really at risk—they’re acting out because they need someone to understand them. Seeing people face to face and accepting them for who they are in that moment—not many young politicians do that.

In youth politics, for a lot of people, it’s about attention. It’s about climbing. But for me, it’s the opposite. I think youth politics can feel really individualistic—like, “There’s an opportunity, it’s mine, and I’m going to kick anyone off who tries to take it.” But I try to uplift those around me and bring them with me on my journey. I’m a socialist, and we need to create change together.

Who I am is a contradiction and pushback to what the system was built for, as well as its misconceptions. The system wasn’t built for women—it took us fucking ages to get the vote. And the system wasn’t made for people of Pasifika descent. But I feel like my whole existence is a contradiction to that. I don’t know if that makes sense.

Honestly, I think contradiction is a superpower for POC. It’s like the ultimate Karen killshot—exceeding their expectations. That you can be an Islander, political, and educated. It’s too much of an overload. And I run into those stereotypes in other youth wings—not naming names, but you can guess who. It’s disheartening. But I can’t change the colour of my skin—and I don’t want to. Can’t change that I have mad curly hair—and I don’t want to.

I’m good with existing as a contradiction to the norm. I’d love to see more of that. I’d love to see governance spaces that reflect the diversity of this country. Will that happen? I don’t know. But I hope so.

Being a young woman of Cook Island and Sāmoan descent in politics, how do you stay resilient against prejudice and hate?

Going to be so for real. A lot of the time, the prejudice and hate comes from your own people [laughs]—and that’s super disheartening. But that’s just the tall poppy syndrome New Zealand suffers from.

I don’t know how I stay resilient, to be honest. But I am very stubborn. A lot of the criticism gets me down. Because I’ve chosen this path of politics, I’ve had people in the community say I’ve betrayed my race, that I think I’m above others. If you know me personally, there’s no way I could ever think of myself like that. #LowSelfEsteem.

There are many days I say I’m going to give up and do something else. And then David Lange randomly pops up and haunts me back into politics. The context of the David Lange thing is—every time I say or think I’m going to give up, he pops up in the most random places. I take that as my sign to keep going, even when I don’t want to in the moment.

The hate can be quite debilitating. I’ve been diagnosed with severe depression and anxiety, and although I’m going through the steps of recovery, it doesn’t mean the hate doesn’t reach me. Social media makes it easy for people to find me, and the easiest target for Karens and online trolls is my race. They assume I exist in this space to fill a diversity quota—that my worth is nothing more than that. And when they find out I have a degree, they double down on my race and get volatile.

It’s been hard with David Seymour and ACT’s rhetoric targeting race, not giving a fuck about equity, and using “equality” to veil racism. They’re not the same thing—and it’s fucked up. People who receive scholarships for equity reasons have to put in twice the effort just to perform at a level others find normal.

I’ve been spat on. I’ve been called all the slurs (even some mistakenly, lol). During my campaign, I had slurs written on my posters—like “get rid of the Bunga.” It’s been isolating. It’s been hard. But I think of my family and little Fania, who just wanted to be warm at night. I want to make sure as many kids as possible are warm and loved. That's what fuels my resilience.

Why stand for the Whau Ward? And why now? What made you decide to step up and represent this community?

Avondale has been my home my whole life. I’ve never lived anywhere else.

Hot take—because I know a lot of young people are about to stand in central politics—but I don’t believe you should stand unless you fully understand the culture, history, and vibe of the place you’re standing in. It's all about authenticity. I knew I wanted to stand for the Whau Local Board, but I didn’t know it would happen so soon. I was encouraged by my cousin, Nerissa Henry, who’s a Maungakiekie Local Board member. She’d been trying to talk me into it for ages, and I wasn’t sure. I was very aware that local body politics is super hard—the demographic is super old—and I didn’t know if I’d have the support.

For the Labour Party, if you want to run as a candidate, you have to go through a whole process. It’s like applying for a job—background checks, CV, cover letter. Then there’s a selection day with debating, panels, and a speech. The ticket gets selected. It was one of the scariest things I’ve ever done—walking into a room full of older people and telling them that local politics isn’t working. That a 35% voter turnout isn’t a success. That the local board needs to be more accessible to young people. And I got selected, which was a surprise.

The whole journey has been super hard—all the layers, emotionally, physically, mentally. I guess for me, I’ve always been motivated by factors outside myself. My drive to step up and represent my community goes beyond me.

My siblings use the parks, playgrounds, and green spaces. They run around and ask me where the water fountain is—and there isn’t one. Something as simple as that would make our ward so much more livable. It would get kids outside and off the iPad or whatever. For me, the whole motivation is the potential of how good things could be.

So that’s why I stood. I’ve lived here my whole life, and I want to improve the quality of life.

A mix of peer pressure and urgency to sort out our problems.

What does it actually take to stand in a Local Election?

Money, lol. [laughs] I am not rich by any means. [laughs] But the sad reality is—to run a good campaign, you need money. And I fucking hate that.

I can’t tell you if my campaign is a good one because I don’t know the results yet. But I’ve found that to get my message across, to get my vibe out there, I need my own materials. When you’re door-knocking and no one’s home, you leave a flyer. Flyers cost money to print.

Running with a political party ticket helps share some of the cost, and you get access to a wider network. Not saying you have to run with a ticket or party—you can run independent. But it takes a lot of mental and emotional energy, which I didn’t factor in. I’m used to running other people’s campaigns—for MPs and such—but running your own is markedly different. You have to market yourself.

You need a good sense of self. Before I started all of this, I didn’t have that. I couldn’t even tell you what I was passionate about. But when you start a campaign, you realise very quickly—people don’t know you. So in order to tell someone who you are in 30 seconds, you have to know yourself really well. I found that out the hard way when someone asked me, “Why should I vote for you?” It’s been super hard sitting down to take this interview to talk about myself [cringes]. I probably couldn’t have finished it like two months ago lol. Even if I lose, I will say I have a better understanding of who I am.

You need a solid support system, because it’s not going to be smooth sailing. Everyone who advised me said it would be easy, or like a hobby. That it would only take up the weekends. But it’s taken over my whole life. I’ve got pamphlets all over my table and house, a billion tabs open on my laptop—it’s just taken over everything, really.

How’s the campaign trail treating you so far? What’s been unexpectedly smooth and what’s been surprisingly tough?

It’s been interesting. I don’t think anything has been unexpectedly smooth—but maybe that’s because, for me, everything is a learning curve right now.

Talking to people has been surprisingly tough. When I go door-knocking, people think I’m trying to sell them a new broadband plan [laughs]. They’re either not home or not interested. And that makes my job hard—because if I don’t know what matters to people, then I don’t know what I’m doing.

It’s been hard to find my voice in all of this as a young person. Especially as Pasifika—when we grow up, we’re taught to respect our elders, not talk back, worship the ground they walk on. So it’s been disillusioning to enter a space where I’m arguing with elders, debating, and tearing apart whatever selfish notions they project or protect. It goes against my cultural way of being and everything I was taught about respecting elders. That’s probably been the hardest part—ruminating over whether they hate me, or if I’ve disappointed my grandparents.

The campaign trail has taken a lot out of me. I’ve been sick for most of it—yeah, pneumonia—but that’s my own fault. I’ve been pushing myself to do stuff when my body’s not feeling it. I always feel like what I do isn’t enough, and I can do more. Which, honestly, is more a manifestation of me wanting to help others more than I help myself.

If elected, what’s the first thing you want to tackle on the Whau Local Board?

Two things in tandem, actually.

The first would be figuring out what the fuck is happening with the Avondale Racecourse. It’d be good to have a solid understanding of the plan—because no one seems to know what’s going on. There’s a lot of confusion, and it’s frustrating not having clear answers.

The second is setting up a Whau Youth Advisory Committee that’s dedicated specifically to policy for young people. I know the Whau Youth Board already exists, but the advisory committee would be different—it would focus solely on policy, while the Youth Board would continue doing all the fun, community-facing stuff they already do.

I think that distinction is super important. Young people make up around 30% of the population in this area—that’s a huge chunk. We need structures that actually reflect that and give young people a say in the decisions that affect them.

With 16 candidates in the running for the Whau Local Board, what sets you apart? Why should readers vote for you?

'Cause I’m not old, lol. I’ve lived here my whole life. I was that kid running away from security guards at Avondale College because my aunt and uncle wanted to cut through to play basketball at the courts. My mates and I would walk home after school, dreaming about the lives we’d lead one day. The Whau is literally scarred on my body from tripping over the fucked-up pavements that no one ever fixes.

I’ve never been a finance broker. I don’t have a business, I don’t have kids, I don’t have a full-time job. My professional life spans a third of the youngest candidate after me [laughs]. I’m inherently different from these other candidates who have a million dollars in their savings accounts and grandkids. I don’t have a lot to gain—I’m putting myself up to receive criticism for three years [laughs].

I’m not going to come in here and propaganda you with “Vote for me.” That’s up to you—to see if I vibe with you. Every candidate will tell you their CV, and for me, most of them have been working longer than I’ve been alive. The system is stacked against young people. They hold us to the same expectations as 60-year-olds.

If you live in Blockhouse Bay, Green Bay, New Windsor, New Lynn, Avondale and Kelston, and you don’t want the same old, same old—vote for me. If you want a local board that’s contactable and approachable, then that’s me.

Can you break down the difference between Princes Street Labour and Young Labour NZ? How are youth wings connected to their party?

First of all, Princes Street is much older than Young Labour. Princes Street has been around for about 60 years, whereas Young Labour is only about 20-something years old.

Princes Street is a special branch, which means it has “special powers” within the party. Most branches are tied to an electorate, but we’re based at the University of Auckland. Our membership doesn’t have an age limit, unlike Young Labour, which caps at 30. Princes Street can include anyone across Auckland, so it’s largely made up of AUT and UoA students.

Young Labour as a whole is made up of youth branches from our six different regions across the country. Young Labour functions as the “conscience” of the Labour Party. It’s there to make sure the voices of young people are actually reflected in the party’s policy.

Fun Fact: Princes Street Labour is one of the four Wikipedia pages that exist about UOA's Student Culture. The others include AUSA, 95bFM and Craccum.

There’s been some debate about national politics influencing local elections. What’s your view on where that line should be drawn?

I think people need to understand that, naturally, there’s going to be some overlap—and pretending the two are totally separate is just dreaming.

National and local body politics each have their own distinct characteristics, and those should be respected. Like, I don’t need the government to fix my pavement—I need them to fix the economy. I need central government to focus on the big-picture stuff, and local government to handle the everyday things that affect my life directly.

Ideally, the two should work together in a way that’s harmonious and effective. If they stop talking to each other, there are going to be major fuck-ups.

Last, if you had a megaphone to speak to every student in Auckland for 30 seconds, what would you say?

"Free Palestine. Land Back. Sanction Israel. Free Indigenous people and decolonise academia. GAF the coalition. Vote."