Interview with the Editors of 'Short / Poto'

The Mighty Short Story, Dual-Language Anthologies, and New Creative Frontiers

I recently had the pleasure of sitting with co-editors Kiri Piahana-Wong and Michelle Elvy to discuss the release of Short / Poto: a boundary-pushing and magnetic anthology of Aotearoa New Zealand short stories. From luscious descriptions of traditional family dinners to incisive commentary on identity politics, Short / Poto captures the most illuminating parts of Aotearoa's diverse multicultural society and its emerging literary scene.

Given the dreadful weather outside, it felt fitting to open the interview with an icebreaker about everyone’s current comfort reads. To my delight, Kiri enthusiastically excused herself from the screen to fetch the library books she had issued earlier that morning, including The Joy of Snacks by Laura Goodman. "Very fitting for exam season," I remarked as she held the title up to the camera.

I then dove into the substance of our discussion, asking what their most valuable takeaway from editing the anthology was. Kiri spoke about the privilege of receiving over a hundred submissions from around the motu, each piece a unique marvel, standing out in spectacularly distinct ways. Michelle highlighted the collection’s focus on the power of language— not only in presenting English and Te Reo Māori side by side, but in showcasing imaginative and diverse uses of language in storytelling. From their responses alone, it was clear both editors had poured themselves into this project.

We turned to the translation process. Both editors worked closely with a team of translators to ensure every nuance from the original submissions— whether in English or Te Reo Māori— was meaningfully preserved. "There is never a precise word-for-word translation," Michelle noted. The imprecision of meaning often became a point of deep discussion. Kiri recalled one moment when a translator questioned whether the verb "boomed" had been intended instead of "bloomed." Though only one letter apart, the difference was significant. After consulting the author, it was clear the soft blossoming of "bloomed" was deliberate— now accurately reflected in the Te Reo translation. It’s details like this that speak to the careful editorial and translation work behind Short / Poto.

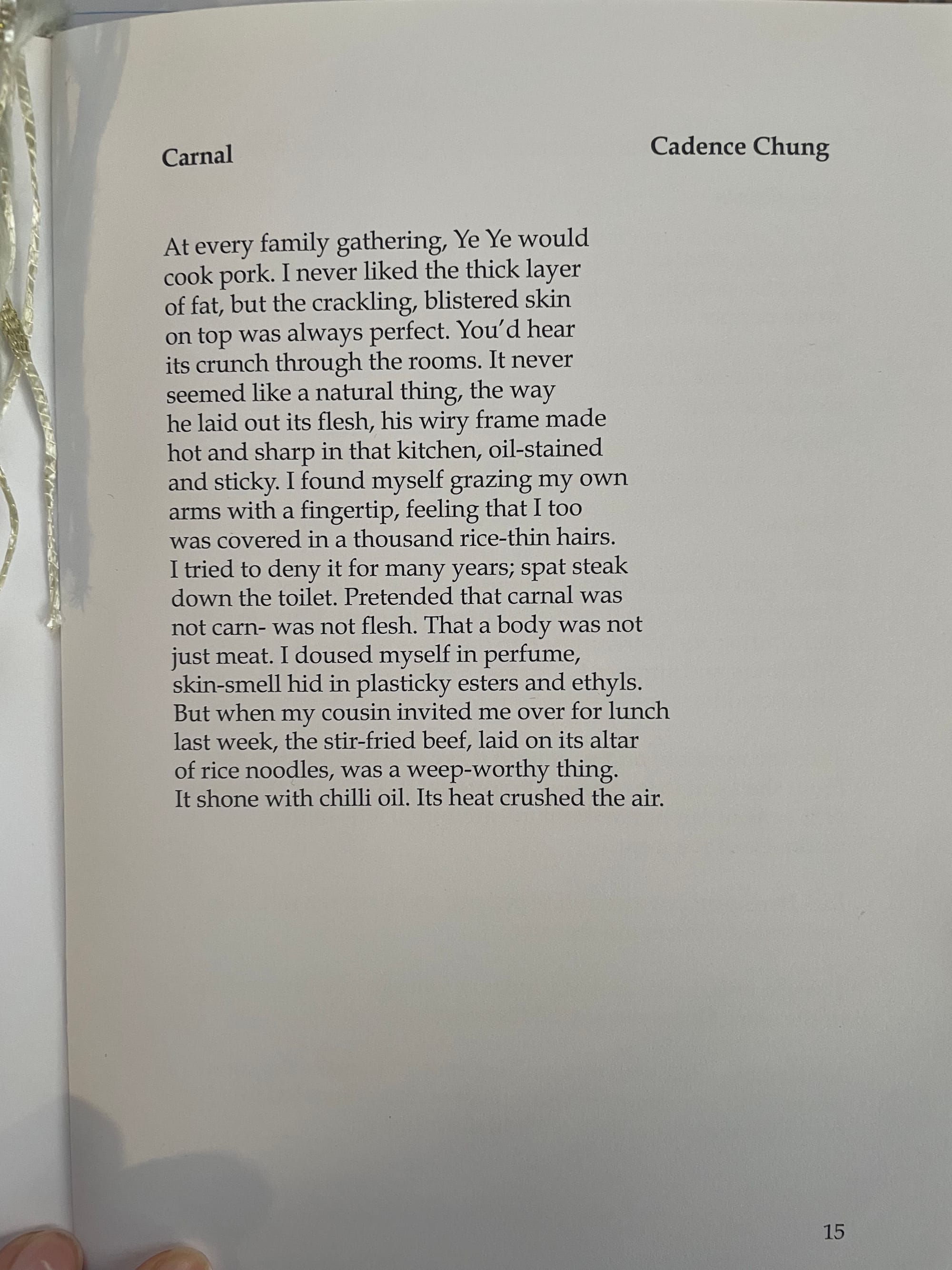

We also discussed the beautiful serendipities that emerged between Te Reo Māori and other migrant languages. Cadence Chung’s piece on migrant cuisine included the Chinese word for grandfather yéye which translators retained in the Te Reo version. But perhaps what resonated most was Kiri’s reflection on the shame often felt by beginner language learners. "That had been the case for me as an upper-beginner learner of Te Reo," she admitted. Despite feeling real excitement and empowerment when first learning a new language, there’s often a fear of getting things wrong. I shared my experience incorporating Te Reo in mock courtroom competitions, where self-encouragement was paired with a deep sense of uncertainty. We seldom talk about these emotional hurdles, but they remain an important part of the language learning journey.

The editors had intended from the outset to publish a dual-text anthology featuring side-by-side translations. But as I noted when first reading the book, the true magic lies in the sheer diversity of voices. Michelle explained how much of the variety in cultural and ethnic backgrounds emerged naturally— an organic byproduct of selecting the most innovative uses of language. The final selection posed one of the toughest challenges, but each chosen piece evoked a distinct feeling on first reading, and many rereads after. That was the unifying trait among all featured submissions.

Throughout the interview, I was struck by how intentionally Kiri and Michelle platformed both renowned writers and fresh emerging voices. One such voice is Lola Elvy, Kupe Leadership Scholar and fellow graduate of our alma mater. Lola writes about the unprecedented issue of our time: climate change.

Lola Elvy – Drought

The wind whispers of forgotten things. We bring ourselves to the table. Time is rich with slowness, the way I watch with anticipation as your fingers press into the mango’s skin, bend its back to reveal the gold inside. As my fingers play around the edges of my glass, I lift it to my lips and sip and picture rain. I think of that day: the way they pressed your skin, bent your back. Did they find your gold? We do not speak of such things. Heavy rainfalls next season will cause record flooding over a thousand miles away, but in two decades, the country will be drained dry. All its water spent. Then we will want someone to blame.

Nā Lola Elvy – Tauraki

Kōhimuhimu ai te hau i ngā mea kua wareware kētia. Ko mātau anō e whakakotahi atu ana ki te tēpu. Haumako kau ana te wā i te pōrori, me he ngākau hīkaka te āhua o taku mātaki atu i a koe i ō matimati e pana atu ana ki te kiri o te hua moheni, e whakapiko ana i tōna tuarā kia huraina ai te kiko kōura o roto. I ōku matimati e wani atu nei i te niao o taku karaehe, ka hīkina ki ōku ngutu inu ai me te pohewa ki te ua. Mahara ai au ki taua rā: te āhua o tā rātau pana i tō kiri, whakapiko i tō tuarā. Ko te kōura rānei te whiwhi? Kāre mātau mō te kōrero i ērā take. Ā tērā tau ka hua ake ko ngā waipuke nui neke atu i te kotahi mano māero te tawhiti atu i konei i te kino o te marangai, engari i ngā tekau tau e rua e heke nei, ka whakamimititia te whenua maroke noa. Ka pau katoa ōna wai. Kātahi tātau ka hia kimi tangata hai uapare atu mā tātau.

Some stories even began as poems. Kiri spoke about the delicate decisions involved— when transforming a poem into a short story enhanced the piece, and when it didn’t. Cadence Chung’s contribution, for example, originated from her poem Carnal, featured in a limited edition of the anthology chapbook, Wok Hei: Aphrodisiac Poems and Recipes in the Year of the Wood Dragon.

Short / Poto is a welcome inspiration for all young aspiring writers. Taking care to avoid narrow labels like showcasing the "best of the best", the collection instead raises a mirror to the face of Aotearoa NZ society, including its inevitable future— our rangatahi. It was interesting to learn about the deliberate editorial choice to cover universal themes (saucy content saved for another day), as Michelle stressed their goal of leveraging the book's wide accessible appeal, with the potential to resonate with adult and secondary school readers alike.

Crafting Short / Poto was far from a static process. Writers had room to adapt and evolve their work, free from the constraints of a central theme— unlike many traditional anthologies. Yet for all its ambition and innovation, the anthology faces a familiar challenge: there’s still no specific literary award category for anthologies. This frustration was acutely felt by Kiri and Michelle, especially Michelle who has dedicated most of her publishing career to editing anthologies. This prompted a broader conversation about how institutional frameworks often lag behind the organic development of creative expression. In elaboration, Kiri discussed how booksellers often prefer clear categories to market books. Michelle noted that even when publishers see the promise of a hybrid work, marketing concerns often dominate the conversation. Balancing these very real economic concerns with the integrity of the creative process is still a live issue for many actors in the publishing industry. I wonder what role we, as day-to-day consumers, play in subverting this dominant narrative of a "tough sell". Is it possible for us to overcome the simplistic pull of a categorical shorthand?

Our conversation about current publishing trends left me wondering, "At the very least, has the New Zealand publishing industry become more receptive to Te Reo Māori texts?" The question seemed especially pertinent for a dual-language anthology like Short / Poto, and its answer could have significant implications for future anthologies or other bodies of work aspiring to carry out the same kaupapa. Michelle described how more books were being translated into te reo Māori, from novels to story collections. A prominent example is Kotahi Rau Pukapuka – 100 books project, a series of translations in te reo Māori of quintessentially beloved texts, ranging from Dr Suess to Witi Ihimaera. And there's Airana Ngarewa's bilingual collection of stories, Pātea Boys. Short / Poto sits among these promising titles and offers something new by showcasing 100 compelling voices of today. Michelle pointed out that although publishers can be wary of anthologies due to marketability considerations, Massey University Press was particularly open to this project. And we are nothing but ecstatic that they were!

Nevertheless, anthologies are uniquely suited for experimentation. "Anthologies almost always sit outside those rules. Anthologies are, by their very nature, rule-breakers," Michelle aptly says. That sentiment resonated deeply with me. Since my teenage years, I’ve adored reading anthologies— flipping through pages of different voices in one sitting. In fact, one of the reasons I love writing for Craccum is the creative freedom it offers compared to my academic work. Short / Poto, of course, is no ordinary anthology. Its strength lies in its linguistic diversity and imaginative storytelling.

We spent time discussing what makes short stories so magnetic. Michelle offered a quote by Luisa Valenzuela, from a 2012 article by Robert Shapard:

"I usually compare the novel to a mammal, be it wild as a tiger or tame as a cow; the short story to a bird or a fish; the microstory to an insect (iridescent in the best cases)."

We paused on that word: iridescent. It perfectly captured the subtle yet powerful way short stories pose questions, suggest meanings, and resist tidy conclusions despite their slim length.

That thought inspired my final question: "If the sky's the limit, what would be your greatest hope for the book?" Kiri hoped to see the anthology integrated into school curricula, inspiring future generations of Te Reo learners. Michelle echoed this, noting Te Reo Māori’s status as an official language and the importance of creative language learning. Rather than sticking to textbook grammar, she encouraged readers to explore language through fiction. Though writing creatively in a second language is tough, the rewards— both personal and cultural— are immense.

Despite these big-picture hopes, Kiri also shared a simpler dream: "If one day, I find myself outside Whanganui, and I see someone reading our book in public…" I smiled as I replied, "If your daydream involved someone reading Short / Poto on an Albert Park bench in Auckland, then you might have already fulfilled that dream." That’s where I first started reading the book, dear Craccum readers— and yes, it was the perfect park bench read.

And so, nearly two hours later, I found myself waving awkwardly at my laptop screen, overflowing with gratitude for Kiri and Michelle. While this article may not be short, the stories in Short / Poto are. They're punchy, poetic, and dense with meaning. Before Ubiq closes its final chapter, open this one. The stories will stay with you long after you turn the last page.