Letter Love

A narrative piece set in colonial Taiwan, tracing a fictional but emotionally grounded relationship between a Japanese official and the Governor-General's daughter, explores the limits of love under history.

When you stand on that island, the first feeling is gentleness. The second time, you might cry—because it is no longer an innocent or timid place. Again and again, we retrieve our love letters from the dark, simply to keep on living.

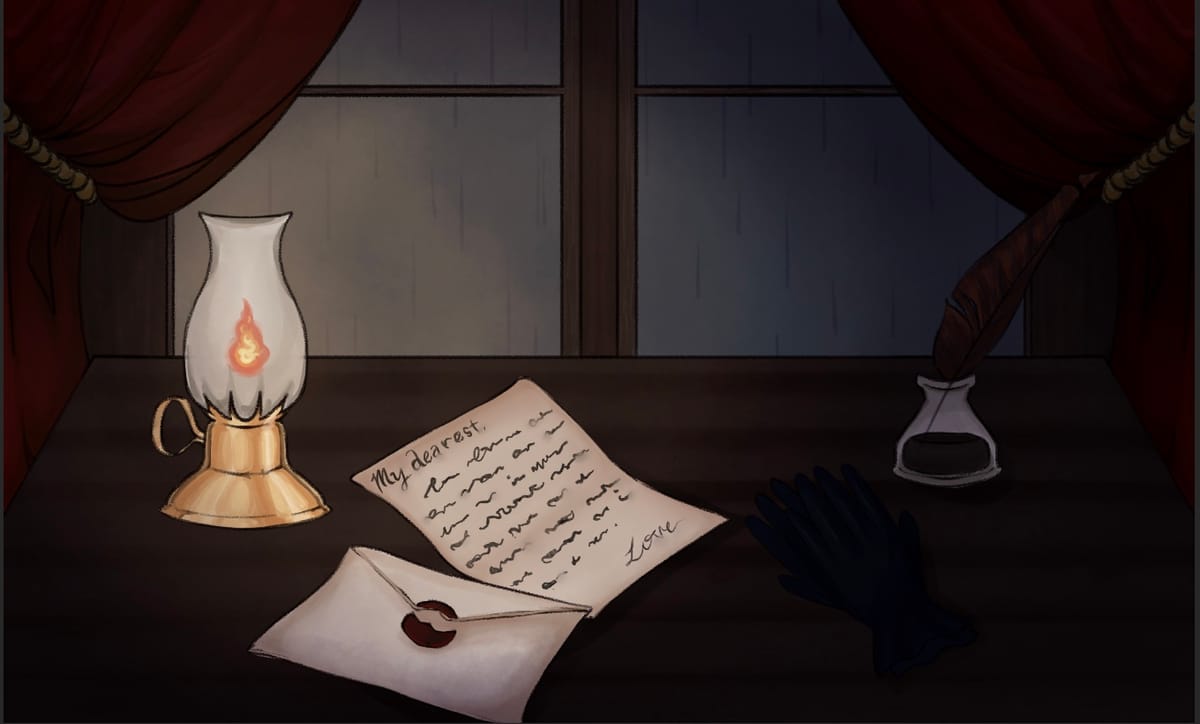

A love letter—when received by a girl, stirs waves within her heart, and her cheeks blush as if brushed by soft pink blossoms. A love letter—it was a wildly popular film from a hundred years ago, featuring a boy peeking at his first love from behind a curtain. You’d think that the snowy white landscape would be followed by the wedding march; but I must apologize to you, because the white ground was meant to cover the tears we had shed. That letter remained unsent, quietly lying in the middle school library—lying there for ten years.

They all grew up. Many have forgotten—not because they were forgetful, but because the hallway of history simply couldn’t contain them.

That winter, I wrapped myself in a thick cotton blanket, lit the fireplace in the living room, the fire casting a shine on my jet-black hair. I wore white fuzzy socks, held a black coffee—familiar to the soul. It had returned. It couldn’t escape. I reached for the graduation yearbook beside me, the yellowed corners and long-settled scent of leather brought it all back again. I stepped into the winter of seventy years ago. Mr. Kawamoto was once a member of the Taiwan Culture Association. He spent his life committed to politics. He always wore a sharply tailored linen suit and his proudest fedora. You’d probably only see this as a mark of upper class status, but you wouldn’t notice that it was made of linen—a quiet reminder to Kawamoto: you are the new pillar of Taiwan. Linen was suited only for Taiwan’s humid and ever-changing climate. Fortunately, he never forgot his own worth. Kawamoto gave speeches everywhere, screened films everywhere, published journals—like Taiwan Minpō. You thought he was patriotic, but what he loved was the self-identity beneath an empire. So his linen suit was one of his last weapons left to resist the world. He was the sun in the love letter. He was also the boy who would sleep forever in winter.

The sound of a typewriter in a café, the flutter of turning newspaper pages, and that gramophone version of “Wàng Chūn Fēng”—they all carried the voice of spring 1938 to Miss Michiko. The voice had been sent. But the boy’s love letter could no longer be delivered. Michiko was the governor-general’s daughter—envied by all. But such a title made her feel suffocated. Michiko longed for freedom, always imagining herself as a bird flying freely in the sky. She read banned books not out of defiance, but because they were her way of resisting the chains that generations had locked upon her. She tried to escape, but she could never flee. She always wore dresses with open collars, while maids laced her inner corset tightly. They would say, “More men will adore you this way, Miss.” But for her, it was a shackle. Of course, she would always carry that lace-stitched handbag and pin up her high chignon with a hairpin gifted by an oji-san, and in her left hand—what she gripped was her last hope for freedom. But that newspaper, it was no longer the old Taiwan Minpō. It was shinan Shinpō under a new name. This was the only breath of relief she could find in that world.

But what you saw was only her polished exterior. What you didn’t know was that, due to the restrictions of class, Michiko would always dash to the daidokoro (Japanese-style kitchen) after the crowd of banquets dispersed—her nearly withered body devouring butter cakes and yōgashi in haste. It wasn’t out of gluttony. It was a scar from her illness. You also wouldn’t know that she had to secretly light the candle she bought earlier that afternoon at Hayashi Department Store, late at night. She couldn’t even buy lily-scented ones—the scent might draw her family near. She was preparing to review a manuscript, meant to be submitted to Fūgetsu Publishing House the next morning.

She picked a sheet of manuscript paper that couldn’t represent her identity. It was bluish-purple, with faint mottled marks that bore the traces of time. Written on it: “Who will come and gently ask me whether those tight-fitting kimono made of silk cloth, folded neatly and stacked on the wooden cabinet, need help being put away?” The kimono (お召し物) and the dress (ドレス) were folded so high, so precisely, as if society believed it was bestowing upon me some kind of omamori —when in fact, they were merely frames of responsibility society had thrown at me, always blocking my view of my own shadow.

The next day, the winter that always headed east and the spring that always headed west encountered each other on the street corner of Honchō-dōri in 1938, at a place called “Shinkō-dō,” which was one of the most bustling spots at the time, surrounded by banks, bookstores, and all the tools for calligraphy. They spoke of the past, the present, and the future; they spoke of politics, aesthetics, and newspapers. They gave each other tokens of love—the girl gave her white pearl, the boy gave his pocket watch.

It was the beginning of first love, but even then they still didn’t know that the American military would soon launch an attack; yet in comparison to the regime that came later under the name of “takeover,” only to rule like a conquering power, that war seemed more like a prelude in the grand rehearsal of history.

They didn’t know the trials that history would leave behind would bury them. They were the hope of their generation, but against imperialism, they were no match. Two budding flowers wilted just the same.

They talked, laughed, and conversed, but what they lacked was that searing intensity and passion…

In the winter of 1940 (Shōwa 15), with the outbreak of the Pacific War, the sky was filled with new sounds—this time they were sharp, piercingly real: air raid sirens, martial law announcements, pressing down all the laughter and chatter of the past so tightly, not even a sliver of space remained. The love letter in the boy’s hand perished with the war and the soldiers, finally turning into dust. The boy never knew that a new era was on its way, and the girl never knew that there had once been a boy who held a letter tightly in his hand, waiting for her arrival. For the girl was spring itself. But to the boy, spring never came, because the spring he longed for had already gone.

The politics they once discussed, the Kimi ga yo (National Anthem of Japan) they once hummed, the visions of the future they once dreamed of, and the love letter they once wrote—all of it was wrapped in a frost of winter, sealed forever in the tears of history. What they lacked was never trust; rather, it was this era that did not trust them.

And that love letter, too—abandoned by an era that could not trust—was left forgotten on a land that had long lost its former glory. Its fate mirrored that of the love letter in a film a hundred years ago—never delivered. As though that old film had warned the people of this island: colonialism is a century-old curse, and the only remedy is for every soul on this island to awaken—only then will the spell be truly broken.

When I opened my eyes, the graduation album in my hand was gently closed once more. But this time, what fell out was a “love letter. I know where it came from, but I do not know whose hands it will one day fall into, nor which stream of history will carry it there. Yet I believe, the sacrifices of the past were meant to take us further—toward a longer, freer path. The love letter has drifted through the island for many years. No one ever truly asked where it was going, because only the people of the island understood that only by continuing forward, by continuing to fight, to refine ourselves, could we attain real strength. The love letter also symbolizes the rise of this era once more—it has walked with us through a hundred years, all the way to this day. And so, in our blood, the shadow of those colonizers remains—not violence, not struggle, but the etiquette, order, sensibility, and tone they once taught us, which we have preserved in our own way. We now carry the soul of our predecessors, but also the face of modern democracy.

The curse is lifted. The love letter is kept by the people of the island.

Yu-An Huang (Lillian)