Lolita, Lure & Lore: Stalking Brian Boyd

A profile of the world’s leading Nabokov scholar at the University of Auckland

Author’s Note

Lolita is a novel narrated by a self-confessed child molester, writing from prison as he awaits trial for murder. All references to the so-called “nymphet” are made with full awareness of its central themes: manipulation and abuse. This recognises the enduring legacy of Vladimir Nabokov, while honouring the rigorous scholarship of Dr. Brian Boyd.

Due to editorial constraints, the piece includes potentially disturbing scenes and images that might not have passed publication, were they not sheathed in euphemism, metaphor and wordplay. It is, in that sense, both a tribute and a test—an homage to the tradition of layering and literary sleight of hand that Nabokov so masterfully embodied in Lolita.

A Mauve Prologue

Look at this tangle of thorns

Brian Boyd reads my first draft and responds with an anecdote: “Do you only write when you’re a little drunk?” The remark came from Edmund White, co-author of The Joy of Gay Sex, at Garth Greenwell’s lush and lyrical prose. Familiar with their works, having read Greenwell’s début novel—an erudite gay expat who lusted after a louche sex worker in Bulgaria—and kept a copy of White’s sex manual on my hard drive, I was unmoored by a simple error: the misspelt name of Mary “Wolstonecraft” that Dr Boyd had flagged.

Dr Boyd has been on my mind, a wandering minotaur in the furrowed maze of my brain, well before our fated tête-à-tête. But who is he to this acolyte, one might ask. He is a towering figure, as Buddhist temples loom long before a shaven monk reaches them. He sports a thick black beard, ascending the crimson-carpeted steps of Montreux Palace, circa 1980, Switzerland. I studied his life and labours in Europe and America, his long-standing love affair with Vladimir Nabokov’s œuvre. A bird of paradise to a jewelled python. And I begin to wonder what secrets, what scandals he might yet share.

And perhaps you, Dear Reader, might pause and ponder: What claim have I to stand as his intercessor, his mouthpiece? Mine is the speech, the satanic verse, and the sordid rhyme. If you can still stand my fancy prose style—I, your loquacious Lucifer in trousers and tweed, now confess each tortured touch, each heinous taste, prowling and pacing between perdition and paradis.

This fevered longing, prurient palate, and ceaseless craving… it all began with Lolita, at the fringe of fading autumn, when my thoughts of her had retreated into the hollows and byroads of memory. The nymphet was summoned in a class on first-wave Feminism, not as a serpentine seductress, but as a dove ensnared. Lolita: a mere sobriquet for Dolores Haze, imposed by our murdering memoirist. Humbert Humbert: the poet-cum-pervert, curator and aesthete to the freshest of the flesh.

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Profane—I chanted like a prayer. Repelled, then compelled by the siren’s spell. These lines were incantations, bewitching the reader’s tongue: taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta.

Disturbed, yet I hungrily devoured each curling line as uncut ramen: saline and slick, swallowed whole, down to the last drop of its briny broth. I wiped the smear from the corners of my mouth, then licked the soupy slick from my fingertips all the same—not a droplet spared. Yum. Though Lolita unspools like a villain’s verse, the wordplays, euphemisms, and double entendres remain perversely pleasurable to decode.

Did Lolita have a precursor? She did, indeed she did. In Lolita’s afterword, Nabokov recalls her foetal form: a short story penned in Russian, “some thirty pages long.” He read it aloud to four friends in one wartime Parisian night. In it, Humbert was still Arthur, ogling an orphaned mademoiselle, unnamed and underage. Nabokov “destroyed” the thing after emigrating to America in 1940. Or so he thought.

Four decades later, Dr Boyd scoured the Nabokov archive in Montreux and found it stashed in an armoire. Across the hallway was room 64—Nabokov’s salon in Hôtel du Cygne wing—overlooking the crescent Lake Geneva and the snowcapped French Alps. But it was in chambre de débarras, room 69, where Dr Boyd sifted through the dust and detritus. There, in a corner wardrobe, amidst files and folders, lay Nabokov’s unpublished lectures and a misplaced manuscript. As Dr Boyd recounts, Nabokov rediscovered Volshebnik (The Enchanter) in 1959 at Ithaca, New York. But its printing would wait after his death, published posthumously in 1986 as a novella.

Lolita, meanwhile, wrenched herself free. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Spring 1947. Nabokov felt her spasms again. A contretemps with some ladies of the Providence Art Club may have jogged Nabokov’s creative spur. This time, Lolita is an American lass with Irish tint in her veins. The nymphet “had grown in secret the claws and wings of a novel.” By 1955, the precocious girl-child took flight under Olympia Press, notorious for publishing lowbrow erotica.

Nabokov despised the character HH, calling him “a vain and cruel wretch” among other dismissals. With Lolita’s taboo topic, he forbade depiction of girls in all Lolita covers. A wish many publishers had since disregarded, perhaps to exploit its salacious subject matter and well-known ill-repute. But what may truly alarm you, Dear Reader, is knowing that Lolita is either you or I. One of us. Surprise. Surprise.

I had seen her twice in films before ever cracking the paperback’s spine. Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 Lolita is a travesty of Nabokov’s printed vision, a diluted farce in chiaroscuro. While Lolita bleeds out whimsical black humour at times, we were served instead a satirised screenplay: a besotted, bumbling beau and a teenage temptress: the very misreadings that hounds Lolita to this very day. Adrian Lyne’s 1997 version, starring Jeremy Irons, fares better in the hue: precise to the parchment. But still, a damsel in flicker and frame cannot rival the poetry of Lolita, with its long-winding, dulcet text that glides along the thirsty throat like the cognac’s fiery rub.

Dr Boyd agrees: “As a shape on the screen… Humbert can never have the force his mind has on the page.” The narrator’s “mesmeric intensity” and the monstrous reality it masks are lost in the theatrical translation. Cinema, alas, cannot replicate the ornamental diction of the Nabokovian prose nor the sinuous mind of its dramatis personae.

Nabokov’s Lolita reveals how the mind can be master of its will yet slave to its desires. | Poster Design by Jewel Agluba

Such words. Such art. Readers were dragged to the sin. Nabokov set a snare, wielding beauty and language as a honeytrap. Or was it the thrill, the drive, the indulgence of our dark desires, that made Lolita so irresistibly alluring? She was banned in several countries, including New Zealand in 1959 (lifted five years later). And yet, Lolita flourished, earning critical acclaim despite, or maybe because of, its checkered reputation. How can something so fair cradle something so foul—and still deserve our love?

I emailed Dr Boyd, requesting an interview. His prominence within literary circles is manifest. In 1979, his rapport with Véra Nabokov, Vladimir’s wife, muse, and fiercely protective widow, granted our preeminent protagonist rare and exclusive access to the sealed Nabokov archives: a privileged aperture into the man behind the metaphor. From that vantage, Dr Boyd wrote the author’s definitive two-part biography, securing his place as the world’s foremost authority on the late luminary’s life.

“This is a surprise,” he wrote, “I thought I’d fallen off the local map.” He’s neck-deep in Karl Popper’s biography—a slow-burning project since 1996. Monday, he’s on campus. He recalls a gay novelist he once introduced at the University of Auckland. Edmund White.

Nabokov scarcely doled out praises. If anything, he flayed his fellow writers with shrewd caustic tang. Dostoyevsky, for instance, was a “claptrap journalist and slapdash comedian.” And yet—by some miracle of taste or temperament—he counted Edmund White, as of 1975, among his three favourite American authors.

In 1988, Dr Boyd presented White to an audience, for his book tour on Forgetting Elena. White is a gay man and a novelist, but considers himself more of the latter. He was surprised that the event was no gay gathering, half-expecting young whiskered queens for fans. To his surprise, he found instead a mix of earnest students and literary enthusiasts. While at UoA, Edmund White revealed that he wrote The Joy of Gay Sex to help financially support his “hetero” niece and her boyfriend. Scandalous in its day for its Kama Sutra-style tableaux of homoerotic acts, the book still retains its charge. (Dear Reader, I dare you to look!)

But their connection went further back. In October 1972, White invited Nabokov to contribute an essay for the Saturday Review of the Arts. The aged author was moved and charmed by White’s overture and mention of their mutual friends like Simon Karlinsky—“the finest of émigré Nabokovians” as Dr Boyd would hail. Karlinsky was then a closeted gay man who thought he was good at being discreet. However, Dr Boyd, ever the sleuth, discovered that Nabokov is aware of Karlinsky’s sexuality, before he publicly stepped out of the closet. Karlinsky, for his part, was fascinated, tickled at the revelation of this juicy discovery.

Intrigued. I quizzed Dr Boyd obliquely whether Nabokov had a “gaydar” or perhaps a tad gay himself to have one (But that, I’m afraid, belongs to a later episode I’m not yet at liberty to disclose.). “How could you say that for a fact?” I asked. Accentuating that Nabokov’s Pale Fire narrator, Charles Kinbote, is also gay.

In September 1973, Nabokov solicited Karlinsky’s opinion of St. Petersburg. “Loud women’s voices,” came the reply, “swearing obscenely.” Afterward, Nabokov’s suspicions churned quietly into butterfat. He turned to their friend, Frank Taylor and inquired: “Tell me, is Simon Karlinsky homosexual? I have a feeling he is. But it doesn’t matter, I like him anyway.” Karlinsky died in 2009 in the loving caress of his long-time companion then husband, Peter Carleton.

Dr Boyd noted that Nabokov has the “astute sense [and] ability to read human nature.” Indeed, Edmund White’s Forgetting Elena, while steeped in allegory, is now widely read as a coded parable of queer desire for acceptance. Nabokov, ever the clairvoyant creative, decoded its allusions way before the critics caught up. On 3 June 2025, White passed away at the ripe old age of eighty-five. Garth Greenwell honoured him in a bittersweet Substack post—the very anecdote Dr Boyd had relayed to me.

“Your writing looks rich and wide-ranging!” Honoured and beatified, I gently opted for an audience at his Edenic dwelling. Dr Boyd graciously suggested bus routes. He preferred bikes and buses to cars. “I think a writer like you would find it more fruitful to see me at home.” I concurred. A scholar’s home has the glimpse and glamour that generic offices and sterile classrooms simply cannot provide. No better place for stalking, I suppose. Without a day’s delay, “Monday,” I said, “would be a blessing, and equally so in your lair.”

Bus. Mid-afternoon. Schoolgirls boarded in droves, heading home. One, a seat just ahead of mine, became my unwitting view. Auburn hair, French braided. She reminds me of Lolita. Coated in faint Eau de Cologne. Tawny motes adorn her nape and jawline. She glances to her side. Long lashes. I imagined Nabokov in a similar seat, fingers twitching on an index card. Scribbling Lolita into being. He, too, would have watched the sulks and snarls, the carrying voices, the insolent guffaws. Jotting from sources like “Attitudes and Interests of Premenarchal and Postmenarchal Girls… Colt revolver, gun catalogues,” and “an article on barbiturates.” Humbert might have espied a demon child, among the innocent throngs. But Nabokov saw that every girl has a bit of Lolita. Humbert scrawls in the fuggy tombal jail: “Lolita, when she chose, could be a most exasperating brat… Mentally, I found her to be a disgustingly conventional little girl.”

“The next stop is…” Ah. That’s my cue. Dr Boyd awaits. Nabokov’s prose, he says, has a “dazzling surface,” beneath which lies “a coral reef of life, hidden caves with buried treasure,” intercutting with the sublime rhythm and rhyme.

Hill. House. A sermon on the mount. The sort of sight pilgrims might gawk at, then genuflect. A bamboo grove rises before a curve. A sleepy stretch of road. Silky oak roots tore the pavement. “Back then, it was flat, now it’s a forest.” A lush botanical garden. An overgrown kawakawa beside an inert sedan; tufted mat rushes perched like sea anemones; bromeliads and succulents, creeping carpetweeds, patches of moss pillowed the concrete with tender green. A pathway leads to a wooden porch. The giving crunch of dead leaves. A carp-like windsock clings to the dapping arms of a magnolia tree. A ping from the door chime. A shade through the glass. Dr Boyd appears: benignant blue eyes of an emeritus, long grey hair, short stubble, and suede brown Ugg boots.

Act 1: Pale Fire

The Irretrievability of the Past

The door of glass and timber creaked open first. “Hello, Justin.”

“Dr. Boyd?” I said, peering through the gauzy screen. He turned the metal knob, smiling in calm ebullience.

“Come on in,” he said, reaching for a handshake. As the narrator and portraitist, I am honoured. I am touched. When I think nobody is watching—I… Oh my, how you have to creep and hide!

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, exhibit number one is what the seraphs, the misinformed, simple, noble-winged seraphs, envied. The learned laureate of Nabokovian lore, matchless in his métier, yet ever proximate to our storied Auckland school, has granted this humble servant of letters an audience and his hour upon the stage.

And so, with no curtain but a creak, the scholar appears; he now steps into the proscenium. He, in. I, out. Ten paces from their ochreous coir doormat, an open room, dappled with ambient amber light: shelves towering to the ceiling in a sepia skyline, books leaning east and west, the scent of woodgrain and paper dust. A blue fleece coat was draped on the armrest; a low monitor glow; and a splash of green from the foliage beyond. Dr. Boyd’s sanctum sanctorum.

“So, this is where the magic happens,” I quipped, drifting towards the hearth, beneath the faux ceiling beams, sighting an ukiyo-e woodblock print at the far wall and some stout Etruscan jar above a nearby cabinet. He has lived here for forty-two years with Bronwen Nicholson, his better half.

“Are these your children?” I asked, gesturing toward the tessellated mantelpiece. Above it, Nabokov’s scaled-up field note, creases, crosses, and a half-veiled wing of a male swallowtail peeking; below, the aragonite bones of a brain coral and a row of picture frames along the ledge.

“Grandchildren. That was some time ago,” he said, leading the conversation towards the dining area. The centrepiece: a porcelain platter with pears, persimmons and Zespri SunGold arranged like a Cézanne still life.

“Your home is picturesque and painterly,” I said, snapping a photo through the limpid panes encased in warm beechwood, spick and span. The radiant golden glow of Ginkgo leaves spilt inward like the morning’s pale fire. He had planted the gymnosperm with Bronwen, who was in the next room (engrossed in scholarly isolation). Dr. Boyd and I took our places next to a honey-lacquered kauri table.

Belfast. 1950s. Brian Boyd’s childhood is embottled in a few misty scenes. He was Burp, plain Burp, in the morning, “...because of the joke I told. If a buttercup is yellow, what colour is a hiccup? Burple.” He was Honk in slacks “...because I was making honking noises in class. I was a bit unruly.” He was Mr. Boyd at Montreux… Véra Nabokov called him “Mr. Boyd for a long time until she read the first draft [of Nabokov’s biography].” He was a Doctor on the honorific line. But to his parents, he was always their boy Brian.

He swallowed a lolly, lodged in his throat. The poor lad was turned belly-up and jiggled like a yo-yo, coughing up the stick and candy. His older sister had fallen into a waterhole on the road where the workmen were working. She came out soaked and shivering from that blasted road. In those hazy gaps, his dad was in the garden, weeding, grubbing, and cupping the cloven earth with bare hands. Then a shard of glass had cut his palm, the delicate web between his wholesome digits. A thin stream of blood welled beneath his pale knuckle.

“Belfast. I was going there in ‘76, and it was at the time of troubles. It was an awful place, really. There was a heat wave in Europe, but it was freezing cold in Belfast. My uncle had bullet holes in his back wall. My aunt took me to a restaurant that had been bombed three times. She said every shop and restaurant in that town had been bombed… at least once.”

1957. Ireland to Zealand. “I used to think that it was partly because my parents sensed the troubles might start again. But I was told by them that that wasn’t the case. So it was just a sense of more economic opportunity…” New Zealand was hungry for settlers, “especially English (British), maybe not Germans because of the war, and the Dutch were ideal in a sense: white settlers. My father signed up for the Royal New Zealand Air Force in 1957.” So they were given a cheap passage. And off they went, down under.

Boyd arrived at a “sandy fibrolite cottage” in a hamlet by the sea. But the waves of mid-century Aotearoa were wintry and wary to newcomers. “I very quickly dropped my Ulster accent… I suppose, I also almost came to feel that somehow I was embarrassed by my parents and their friends who had an Irish accent… I wasn’t a rugby-playing kind of kid. I liked to do rough and tumble, but I was never really good at sports. So, I didn’t fit in that side of Kiwi life…” He paused, “People, kids especially, were very intolerant of differences in those days in the ‘50s.”

Lolita, as Dr. Boyd observes, is Nabokov’s attempt to establish himself as a local writer in his adoptive homeland (a deracinated nobleman’s effort in assimilating amongst republicans). Like him and yours truly, Nabokov was an émigré who left his native Russia following the Bolsheviks’ imminent advance. He then fled France when the dark clouds of Fascism had trundled upon Europe. Humbert, with menacing brows, casts his eyes across the Atlantic: “America, the country of rosy children and great trees, where life would be such an improvement on dull, dingy Paris.”

Lolita was set in the American milieu, mountains and motels, highways and hinterlands, where the hungry Humbert the Hound, in his moral frailty, allowed lust to unbuckle his belt and let libido slip its leash, leering lecherously at his puerile prey from the dark, drugged her unconscious, defiling her on sullied sheets in rented rooms, on a sick sexcapade from sea to shining sea.

Humbert narrates an instance of a row with little Lo: “…at a motel called Poplar Shade in Utah… my Lolita… asked, à propos de rien, how long did I think we were going to live in stuffy cabins, doing filthy things together and never behaving like ordinary people?”

It makes one wonder, could Nabokov have crafted the same transgressive novel as Lolita had he migrated to Aotearoa? Dr. Boyd said, “he would have set it here, although it would have had a different structure because [a paedophile] couldn’t keep on the run in New Zealand.” Humbert would have to restrain Lolita in a basement or a muffled room (which I find even more horrifying). In Lolita, Humbert spoke of a “self-made seraglio” while he plays as “a radiant and robust Turk… enjoying the youngest and frailest of his slaves.”

Although Humbert’s gaze dominates every scene, Nabokov has artfully suggested that not everything is what it seems. The wit and lyricism are marred by glimpses of cruelty. Lolita’s silence speaks louder than Humbert’s prose. | Poster Design by Jewel Agluba

From here, Dear Reader, we asked what lured our featured figure into Nabokov and literature.

At nine, his mother enrolled him in elocution lessons. “She thought I mumbled. There, I got to understand both grammar, voice production and literature in a way that I wouldn’t have otherwise… several steps ahead of my classmates in that respect. English was always very easy for me.”

In Canterbury, he thought of pursuing history but “found it very dull” and English “very rewarding.” And then, “there was a girl I thought was very attractive and was doing American studies.”

“I hope she’s your wife,” I bantered. He rotated his ring of gold with his crêpey, tender phalanges, sliding it between the basal and median knuckles, cradled in a plump coronet of flesh. I sensed those annular veins, warm and throbbing still, with same fire and kiss, in the nine lustra of connubial bliss.

“No, no. She was out of my league.” No luck. One-sided. Clandestine. But with the lovely lass in class, and cupid’s fickle quiver and teasing little arrow, he took up American studies six weeks into first year and never looked back.

But what of Nabokov? Our Learned Reader might ask. I shall reply. It began with Lolita. In point of fact, there would not have been Dr Boyd if he had not read, one autumn, some initial pale fire. Oh when? About as many years as Humbert was that summer he met Annabel Leigh, in the French Riviera, in a princedom by the sea.

Who is Dr Boyd at a closer look-see?—“Oh, I won’t tell you that...” He japed then laughed. With a fruit tableau before us, laid like a Cézanne masterpiece: “…but when I eat apples, I eat everything, except the stalk.” I imagined his cuspids and molars work through pear and persimmon, as he lathers the bits with his enzymes, and masticate. To devour the seed and skin, pulp and all, what a method! Then he adds with a dash of mirth and mischief: “You know the Zen koan? What’s the sound of one hand clapping? I can…” He demonstrated, flapping his fingers against his palm with the wet slaps of a grey seal applauding itself. It sent my tiddles atwitter.

But behind his jocular mask is a writer’s nib, sharp enough to draw blood and splinter brittle bones. “Do you only write when you’re a little drunk?” (Hemingway wasn’t exactly sober writing The Sun Also Rises.) Dr. Boyd is, by temperament, “naturally critical and undiplomatic,” he wrote in Stalking Nabokov. As the exalted Nabokov used to say with Faulkner, Camus, and many other totems and potemkin, they’re “complete non-entities insofar as my taste in reading is concerned.”

“I don’t care for Dostoyevsky at all,” he said. “I find his writing clumsy and hysterical.” Joseph Conrad? “A terrible writer. I find [Heart of Darkness] an appalling book. That enforced dreariness…” he paused, then struck, “as Nabokov put it: buttering buttered butter.”

Gabriel Garcia Marquez: “Sumptuous, but it doesn’t really attract me.” Kazuo Ishiguro: “Another writer I don’t care for.” George R.R. Martin: “I don’t know him.”

For Dr. Boyd, Nabokov is the crème de la crème. And when asked: “If not Nabokov, who’s the better writer?” He offered only one name: Shakespeare. I suspect even that was a reluctant compromise.

Boyd reveres Nabokov’s ability to break the scene, to leap from the metes and bound of one’s mind. “Tolstoy keeps you in it,” he explained. Nabokov lets you rise above it.

“If I could write like Nabokov, I would,” he sighed, “but I try to be as clear… and pack as much into a sentence as I can.” He looked down at his hands. “I wrote the Nabokov biography hoping my parents might be able to read it. They picked up the book—and didn’t get past the first page.”

Both his parents left school at fourteen, in the Great Depression, to support their families. In the seventeenth century, the Boyds were part of the Scottish settlers during the Cromwellian conquest of Northern Ireland. They were Presbyterian in a Catholic majority Emerald Isle. “My parents were religious in their upbringing… when we were children, they were fairly strict… My memories of my grandparents were fairly forbidding… I didn’t have that many memories back in Ireland.” But he remembered this well: the moment when Lolita first landed in his lap and Nabokov came striding into his taciturn living.

1965. Palmerston North. A grocery. His father would work there early mornings and late evenings, and report to Base Ohakea in between. His mother would manage the dairy for most of the day. But Brian’s prodigious appetite for letters became unquenchable. His parents purchased “a bookstore with a lending library” for him to consume.

There, one day, a patron recently returned a copy of Lolita. Boyd was thirteen and tempted. He sidled and smuggled it past his Puritan parents and stashed it below his pillow when they weren’t looking (naughty).

Lolita, that Lolita, my Lolita. There she was in that Weidenfeld and Nicolson release, Sue Lyon in dustwrapper, coiffed and preened like a waxen figurine. Boyd scanned from the blurb, V.S. Pritchett and Graham Greene, the words like sex, dirty, sin and distinguished. Oh, saccharine. The hunter chasing and carousing, that nymphet, that tigress, that coquettish colleen; only to find she was no aphrodisiac, but a grandiloquent guillotine: “It cooled my libido and overheated my cranium.”

Humbert crafts Lolita's world in his own ornate image, yet fickle McFate reminds us that even the most eloquent murderer cannot woo his destiny—or the violence that undoes him. | Poster Design by Jewel Agluba

By now, Gentle Reader, you know who Humbert was. As all mimes and mummers had preached and spouted: he came to America, abducted Lolita, harboured a penchant for the pubescent sheila, and starred in some fiendish domestic drama. Let it be known that Humbert has the utmost regard for young girls, their innocence and purity. Humbert was perfectly capable of intercourse with Eve, but it was Lilith he longed for. Not every callow and comely maiden is Lolita, mind you, they were only few—the crust of crème brûlée. A certain species, a hussy, a vixen, a minx, he called nymphic. A “demon child” he says. A nymphet.

Lolita’s first tingle came not from flesh, but from furry hands of an ape in Paris, the Fifth Arrondissement (in the city’s garden zoo), who, when asked to draw itself, shaded no face nor form, but the grilles of its cage. This is where the inmate Humbert came to be. But the nymphet, that hapless pet, could have been mothered by a demoness. Nabokov composed a poem called Lilith (1928) to “amuse a friend” but quickly warded readers off “from examining this impersonal fantasy” from his later novels. But shall we pay heed? Nein! What fun would that be?

In Lilith, the poet dies in bloodied coat, and wakes among the fauns as Pan-shaped deities in bucolic afterlife. There he met a naked, slender girl (the miller’s youngest daughter), seeing her rosebuds roused, a new-grown garden blushing, and moist moss trailing down her brooks and paddocks. When his coat burst to flame then ash, he advanced to green-eyed Lilith, sprawled across a Greek divan. She stroked his emberhead and beckoned him near. “How enticing, how inviting, her moist pink rose!” And with a howl feral and hardened, he descends upon Lilith, like a snake to a Gorgon’s lair, suckling the syrup and seed of that forbidden fig. But at the sobering rush of semen, and the peeping crowd who had watched it all, only then did he understand: the poet had been in hell all along.

Was our Lolita Lilith incarnate? You, in the gallery, be the judge. Lilith bears her blood and sinew, a semblance, a shadow, a jumping gene. Nabokov rehearses his theme of the forbidden child. Her ontogeny is thus as follows: The succubus of Lilith. The incubus of Volshebnik. And in Lolita? The nymphet—cunnus diaboli? An infernal trinity. The sow, the swine, and the unholy sprite. Lo. Lee. Ta.

But beware, beware, Reader mine, the devil is within the impish line. Dolores Haze was stripped of her free mind, dressed as a doll of desire. Nabokov implores readers to riffle through Humbert’s mendacity and misdirection. Lolita is like any school-age girl. Standing four feet ten in one sock. But her budding feminine virtues, under Humbert Humbert’s predatory pretences, were tempered, distorted, and irrevocably corrupted. Lo–Lee–Ta.

As Dr. Boyd averred: “Nabokov invites the good reader of Lolita to see Dolly Haze and her pain in ways that Humbert can’t see or chooses to ignore. Some people, even some distinguished readers, have tended to read only Humbert’s Lolita; but Nabokov’s Lolita, with all its additional ironies and pathos and indignation, anticipated #MeToo by more than half a century.”

Humbert’s deviance is pathologically accurate. “Yes, it seems to be a common pattern for paedophiles. I have been in correspondence with sexual abuse therapists, and they can’t praise Lolita enough for the accuracy of the perpetrator and the relationship between them,” said Dr. Boyd. Humbert’s failure to consummate his passions for his coeval, Annabel Leigh, had marked him so profoundly and insidiously.

Yet again, this curious host is left to muse, and be bemused. Have you ever wondered, Sweet Voyeur, why the prologue is coloured mauve? Not quite purple, not quite rose. A liminal hue, wistful and morose. The tincture of a tremor. A memory’s sore blush before the bruise.

Nabokov inherited the palatial Rozhdestveno manor, erected by the riverbend of Oredezh, from Vasily Rukavishnikov, whom he affectionately calls Uncle Ruka. In Speak, Memory, Nabokov describes it as: “white-pillared mansion on a green, escarped hill and its two thousand acres of wildwood and peat-bog.” In the summers, young Nabokov would see his Uncle Ruka, his swooping moustache, bobbing Adam’s apple, dandyish demeanour, half a dozen valises and violet boutonnière. He leads young Vladimir to the closest tree, with a “small, mincing feet in high-heeled white shoes,” a tender hand picks something from the low branch and says in French: “For my nephew, the most beautiful thing in the world – a green leaf.”

Vasily lived a casual and foppish life. His affections, especially for his handsome nephew, hinted at a queerness unusually visible for the time. At eight or nine, he would draw the faunlet on his lap, then fondle and caress preteen Vladimir with crooning sounds and fancy endearments in the view of young footmen clearing the dining table. “I felt embarrassed for my uncle by the presence of the servants and relieved when my father called him from the veranda: ‘Basile, on vous attend.”

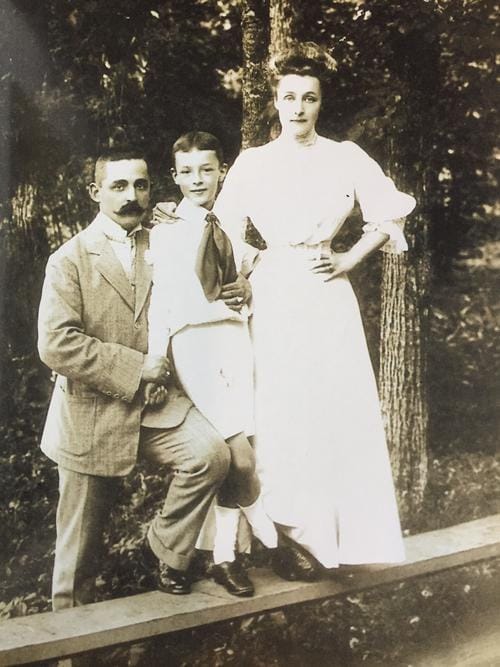

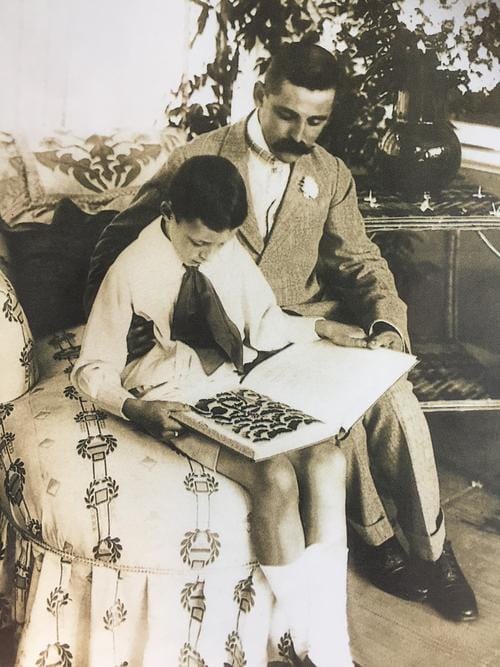

In a sepia print, young Nabokov stands in contrapposto on a wooden plank. His mother, Elena, poses left hand akimbo. Uncle Ruka clasps the boy’s wrist and waist with the same studied intimacy seen when they sit together on the boudoir settee. Nabokov’s early unease with his Uncle Ruka might have informed Humbert’s fixation on touching Lolita. So, it begs one to ask la question du jour: was Uncle Ruka’s rub and pat the poison from the wound that remained ever open? Well, let us grope and hope.

[1] Vladimir Nabokov (centre), his mother Elena (right), Uncle Ruka (left), Vyra, 1908 | [2] Vladimir Nabokov and Uncle Ruka, 1908 (Image source: The Nabokovian)

Despite Uncle Ruka’s “colourful neurosis,” he was no more than a social dilettante. “Nobody took him seriously,” Nabokov writes. When he died alone in Paris in 1916, “it was with a quite special pang.” But his earthly fortunes went to his favourite nephew. The seventeen-year-old Nabokov inherited Uncle Ruka’s rubles and a two-thousand-acre domain. But the boon didn’t last for long. Following the 1917 October Revolution, Nabokov would lose the Rozhdestveno manor, the only real estate he ever personally owned, and would never see it again.

Boyd, too, would leave their Belfast house, his birthplace, with the groan and gasp of the era’s diaspora. “I didn’t crave going back there.” But he scouts the place on Google Maps, “I’ve seen it and it’s a strange experience.”

Palmerston North. 24 May 1969. Boyd’s Bookstore. “On the narrow mezzanine looking into the rest of the bookshop, I checked off Time magazine.” The cover’s with butterflies and St. Basil’s in the background, Nabokov’s imperious hauteur, bald marble dome, and piercing gaze look back. Headline: “I have never met a more lonely, more lucid, better balanced mad mind than mine.” Brian, athirst and afire.

He dashed to the city library. He pulled Pale Fire from the shelf. He read it, as he said, “with more enchantment and exhilaration than anything” he had ever touched. Each fresh blast of discovery stoked his torch of passion. It was ineffable, no mortal tongue could utter. Now, a greater endeavour lures him on: to fix once for all the perilous magic of Nabokov.

I must tread cautiously now; enunciating in deft strokes the furtive moans of delight. As the great authors of antiquity counsel their novice, “Let the readers imagine”, and so on. And yet, on second thought, it would never do, would it, to properly impart, with luminous intensity, the maddening tug of those redolent sensations, the galvanic throb that a priest of Venus alone can arouse. You have to be an artist and a madman, a creature of infinite melancholy, so chronically untouched that the merest accidental brush of its raw, electric hands against your bare limbs sends a jolt of longing straight to your hollow groin. Had I been a painter, Dear Reader, this is how I would guide the brush upon the easel and map the mise en scène:

There would have been a bower with ferns, vines and blood-flowers. There would have been hummingbirds drinking from a mouth of nectar. A lavender field abutting the summer sky, bumblebees tumbling in the wind like pollen and dust. There would have been a dab of carnivorous sundews, deciduous elms, red-dotted apple boughs bowing over the glimmering grass, a golden spaniel careens towards the opalescent woods. There would have been an island in a coral-ringed pool. A hammock in Bora Bora. A bonfire by the beach on a cool, starry night. Acrobats. Jugglers. Masquerades. Mimosas. A Samoan fire dance: twirling, tossing, and thumping with a lit machete or baton. Wreaths of Arabian jasmine. There would have been rows of gaudy spectacles. Hearty howls. Holy oils. Harvest Moon. There would have been the rhythm of the waves. A damp white cove. A lover’s parted lips gathered on a hot lobe of ear. And then: she smelt almost exactly like the other one, the Lolita one, but more intensely so, with rougher overtones—a torrid odour that, at once, set the girdle astir.

He was still only a boy. But the nerves of pleasure were laid bare, a super-voluptuous flame was set permanently aglow in Boyd’s subtle spine. “I followed all those cross-references. And if you follow the first trail… you’ll find out that Kinbote is the narrator… ex-king of Zembla, that he’s mad and doesn’t quite realise it and… he’s a homosexual.”

Before then, he considered either acting or academia. “I was a reasonably good actor for my school, but I don’t think I had the passion for it…” Instead, he found Nabokov. He found literature. And in that world of high art, he finally felt… home. He was dux in Palmy and excelled in Canterbury. He never thought of leaving literature behind. Now, as a septuagenarian, I asked: what would you say to that young Boyd, thirteen and tempted, sixteen and sated? He glanced and smiled: “Keep at it!”

Frigid, gentlewomen of the jury! Brian Boyd had thought that months, perhaps years, would elapse before he might find true love, but by thirteen he was wide awake, and by sixteen he was technically in love. Dear Reader, I am going to tell you something very strange: it was Pale Fire that seduced him. Not Humbert nor Lolita. Pale Fire. And with that, and a bush of beard at seventeen, our Boyd would cease being a boy-child and would turn into a “young boy,” and then, into a “college boy”—the horror of horrors!

To be continued…

This article was first published in Craccum Issue 8 - 2025.

If you or someone you know is experiencing sexual abuse, support is available. Call Safe to Talk on 0800 044 334, text 4334, or email <support@safetotalk.nz>.

If you’re in Auckland, you can also reach out to HELP Auckland on 0800 623 1700 for free, 24/7 confidential help and support.