NZIFF 2025 Craccum Coverage | Abraham's Valley

Between stillness and inevitability, Abraham’s Valley renders existence as a long pause before the final 'cut'.

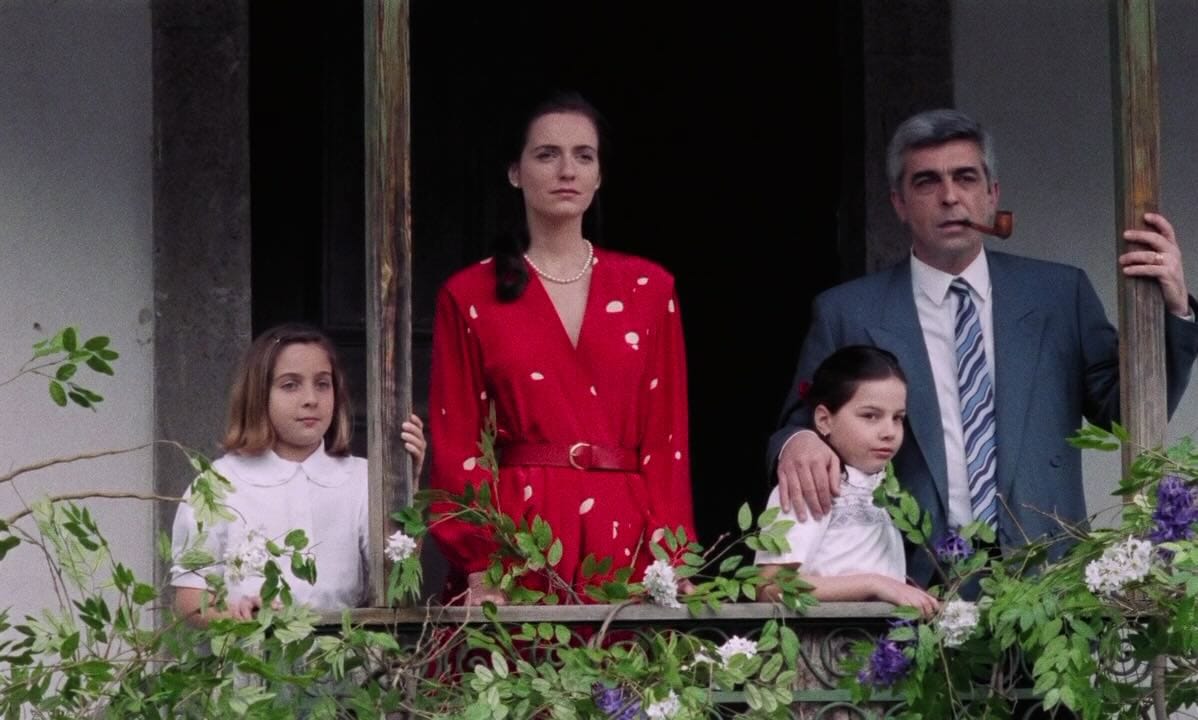

Abraham's Valley is an adaptation of Madame Bovary in the form of a novel commissioned and written by Agustina Bessa-Luís. This novel was expressly commissioned by the director himself in place of a traditional script, and was later adapted by him. In the opening shot, the ancient serenity of the landscape and the narrator’s highly literary voice-over seem to transport us to another time—let’s say, to Flaubert’s 19th century. But the train immediately brings us back to the present. This opposition between old and modern, presented right at the beginning, is one of the film’s hallmarks. Indeed, modernity constantly intrudes, jarringly, to place within a contemporary chronology a story steeped in 19th-century atmospheres—or perhaps it would be better to say: timeless. Through the narrator’s voice, through certain dialogues, through certain scandalously modern objects (a speedboat, a scooter, a sports car) that appear now and then, almost casually, to interrupt the film’s dreamlike flow, we learn that the story unfolds from the 1960s to the present. But is that really so?

- Adriano Aprà, In deception lies the wisdom of De Oliveira and his implausible Madame Bovary, May 1994 [text translated with ChatGPT]

Impenetrably simple. I can't think of any other way to describe how this film washes over you in its serene inertia and measured narrative tempo, suspended in time for three and a half hours.

I remember watching an online DVD rip of this film months ago and having to stop an hour in because the film felt too overwhelming at the time. Having to keep up with voice-overs reciting dense prose laid atop de Oliveira's thoughtfully composed and painterly compositions made it feel like I was cheating the film of its deserved attention. You can't afford to have your mind drift away from every piercing, philosophical and comedic commentary our unnamed narrator provides and delivers at the most precise moments in every scene. Even then, the words escape from your consciousness anyway. I have nothing else to add to the existing laudatory discourse of Abraham's Valley except vehement agreement. It's not every day you come across a film so confident and straight-faced about its conceit to sustain your attention without appearing gimmicky or distracting. The omniscient narrations speak with contemplative certitude, a voice of opposition and affirmation within a given scenario. People are not kidding when comparing the experience of this film to reading a good book. But like most books—or literature in general—how do you cinematically depict the turn of the page, the momentary blankness of thought paused, the anticipation of what will be revealed next in relation to the previous pages of narrative storytelling accumulated up until this point, the stilled precipice of potential change?

Narrator: Her beauty surfaced upon the silk of slumbering hurt. She was like a wild beast without food, an animal, a tiny creature, but with already predatory looks. She knew that her ties with mediocrity and her love of childish ways were broken. As she unbound her hair, her heart, too, was unchained, though she found comfort in constraint, and that was gone forever…

Images courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

Images courtesy of National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa.

To propose an obtuse comparison, Michael Snow's 1971 experimental film La Région Centrale (also running a similar three-hours long), a film that essentialises cinema down to its basic constituents—movement localised within a given space and its capture through the rectangular border of the camera frame—is not too dissimilar to Abraham's Valley in exhibiting this nauseating feeling of suspension, of only being able to move or interact from a singular three-dimensional vanishing point, 'the central region', we are incapable of seeing ourselves through ourselves. The camera and our Bovary-inspired protagonist, Ema, are one and the same. Our limited depth of field in understanding those outside of our perception can only be satisfied once we make the definite break, the severing, the 'cut' from one image to another, escaping the confines of the still (moving) image and towards the infinity(s) of possibility. For cinema, it's simple: physically cut the film strip using scissors and splice each bit of celluloid together with tape, or hit Ctrl+B on DaVinci Resolve. For Ema, and by extension, the rest of us who also live in our own little prisons, the method is much more grave and irreversible: death.

Michael Snow, La Région Centrale, 1971.

Ema desires the beauty of sororal belonging and stability, but is condemned to be desired by the lecherous whims of the male elite circles she has married into. She fights fire with fire, her adulthood comprising her futile attempts to symbolically mould herself into desire incarnate, a male desire. She cuts not to a different image (of herself), but to another identical image, one image after another, one tryst after another, one dinner party after another; splitting oneself to become oneself. She cannot escape her circumstances, the horror of one's fate sealed in the heavens. In the same way one is given the choice to treat their lung cancer with either Lucky Strikes or Old Golds, Ema is caught between the more familiar expectations of becoming a devout, chaste Christian just like her late grandmother, or enjoying the ephemeral, aesthetic life of 'independence' as a socialite befriending dignitaries, mayors, writers, and opera singers. She is thus trapped, suspended in the indeterminacy of determinacy; she knows she is doomed, but it now becomes a matter of 'when' and 'how', a matter of how long she can bear this unchanging image of herself for longer.

In a fatalist universe, there is nothing else to see except suspension…

Images courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

To continue on Aprà,

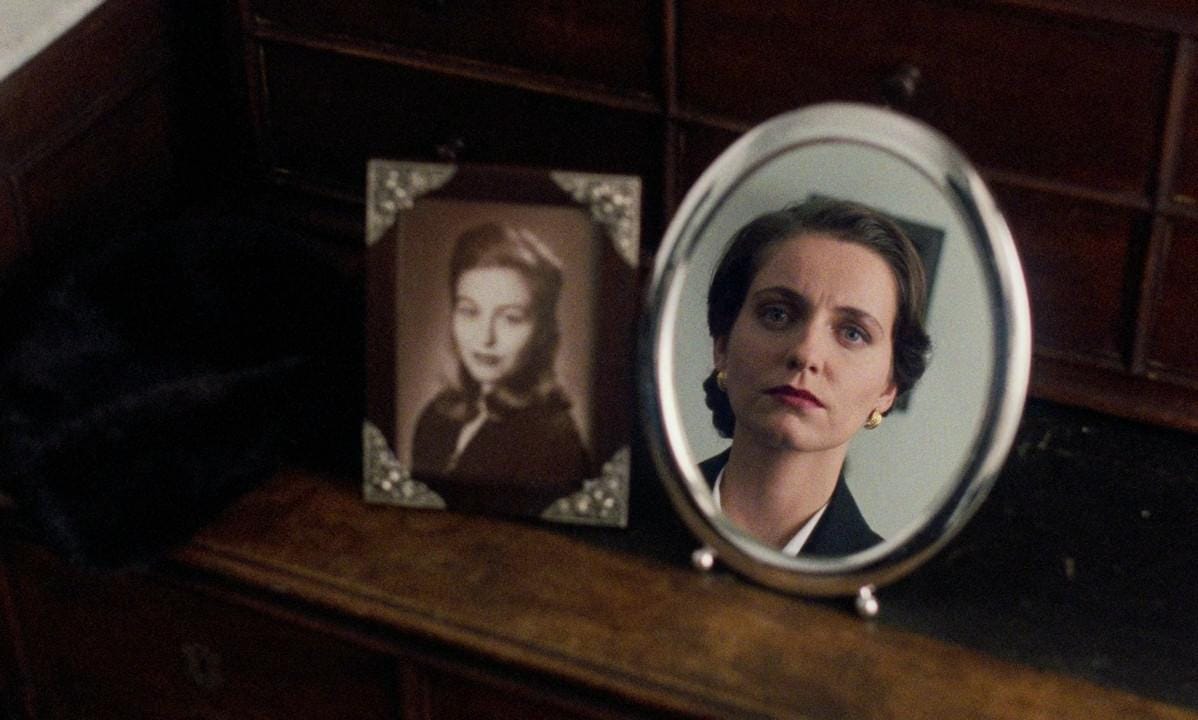

Emma is beautiful: so said all the men who looked at her, each with his own idea of what that could mean, and yet the assertion of a beauty that has no roots on earth was common: such for the liquid blue of her eyes, which allude to a mysterious depth we can never touch; it is the void, it is the infinite, which is not of this earth. Emma is the instant, she is the “photograph”: for this reason we see her framed so many times in a mirror, echoed by other portraits, by other photographs. She crosses the film like a sleepwalker. She is a passive object of desire, not passion. She is no different from the aseptic world that surrounds her… What, then, can this ghost surrounded by other ghosts rebel against? In such a disembodied film there is no history, no society, no classes. Emma Bovary’s drama was rooted in the concreteness of things; here we are instead suspended in the ethereal world of ideas. The actors do not interpret a character, much less embody one; they do not act: they quote. They allude to something outside of themselves, presenting themselves to the spectator as shadows of something. The spectator is placed in an uncomfortable and unusual position because they are deprived of any tactile and concrete relationship with the images. They are nothing but the momentary and perishable materialization of suspended instants: life itself is a mental film. After all, what is a film if not evanescent shadows that delude us into living a life that is not ours? Then the strangeness of this film would be nothing other than the intact and aching essence of every film: the illusions that persist over time, beyond time itself, in the memory of images seen, phrases spoken, presences, absences, of life and beauty, in its duality.

Images courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

I'll conclude this piece with an excerpt from my favourite exchange in Abraham's Valley between Ema and arguably the only man who doesn't actively pursue her sexually, Luminares. Ema, consistent with her disposition to rebuff every man who has ever flirted with her, replies with quickfire prickliness, a defence mechanism she has mastered all her life. Nevertheless, Luminares remains lethargic and reserved, coolly certain of the uncertainty of his thoughts devoured from a lifetime of reading. It's a pastime that might as well be a better alternative to the chauvinist philandering of his contemporaries. The narrator, too, makes blunt assertions about Ema's character; sometimes they are detached observations, and sometimes they side with specific characters. No element is neutral in Abraham's Valley. Everyone and everything proposes axioms against one another to orient themselves, from themselves.

To prove that I can see something, there has to be 'something' directly in front to direct my attention to. Thus, the "I" and "something" simultaneously become proofs of each other's existence. The tragedy is that you can't orient yourself from yourself. That's what dying is for, the ultimate axiom.

Narrator: Luminares told the story of his aunt Alberta, who had her hair washed on her deathbed. She was half dead. Water dripped off an oilcloth and soaked the towels.

Luminares: She chose a tint, but wouldn't look in the mirror… The sensualness of things that comes with death, that's what she must have felt. Only a woman could do that.

Ema: But I am a man, according to you.

Luminares: Flaubert said, 'I'm Madame Bovary.' And Flaubert was a man.

Ema: They call me 'Little Bovary,' but I am not her. Still less Flaubert. We share the same first name, Ema, that's all.

Luminares: A Cardeano at birth, a Paiva by marriage. Ema Cardeano Paiva.

Ema: Are you mocking me?

Luminares: No. I speak with unhealthy affection. Don't be amazed to see tears in my eyes.

Ema: I have no future.

Luminares: Don't be big-headed.

Ema: I am not big-headed. I am all in the past. Only the past lives in me.

Luminares: You say you don't have one, but your fate is your fate. The bottomless well of desire…

Ema: You are implacable.

Luminares: Life… Life is implacable. Not me…

(…)

Narrator: Luminares wondered whether Ema would not have made a good La Valliere. She even possessed the flaw that stimulates beauty in the eye of corruption. Satan too was lame. Beauty must contain a warning if men are to be safe. Ema tasted evil as if it were a delicacy, a wine many times strained, passed over years from barrel to barrel, rounded, strange, deep. A criminal record of sorts, that badness which a woman involves in everything, her pleasures, duties, contracts and suffering. You couldn't imagine her doing harm, though she might dip men's hearts in a spice that gives the earth salt and makes it fertile…

Images courtesy of Cinemateca Portuguesa – Museu do Cinema.

Abraham's Valley | Clip | NZIFF25

Follow our Letterboxd and Instagram to get live updates and reviews directly from our dedicated student team of film aficionados <3

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in Craccum are those of individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial team or the publication as a whole. While we aim to ensure accuracy and fairness, Craccum cannot guarantee the complete reliability of all information presented and assumes no liability for errors or omissions.