NZIFF 2025 Craccum Coverage | Kokuho

There's an imbalanced relationship between the art, the artist, and the viewer.

For the viewer, the appeal is clear: art is transformative in where it takes us, for a moment, we are consumed so viscerally. Unable to take our eyes from where they lay, dare we blink, in fear we may miss the strokes of passion painted in front of us.

For the artist, however, the appeal is less clear: Art is pain, whereby pain is transformative in the sense that it takes us to the lowest, darkest points of our lives. The artist is consumed so viscerally by the art that they lose all grounds on which they stand, and on whom they stood next to. Unable to take their eyes from where they lay, dare they blink, in fear they may miss the strokes of artistry they have spent every waking moment building up to brush.

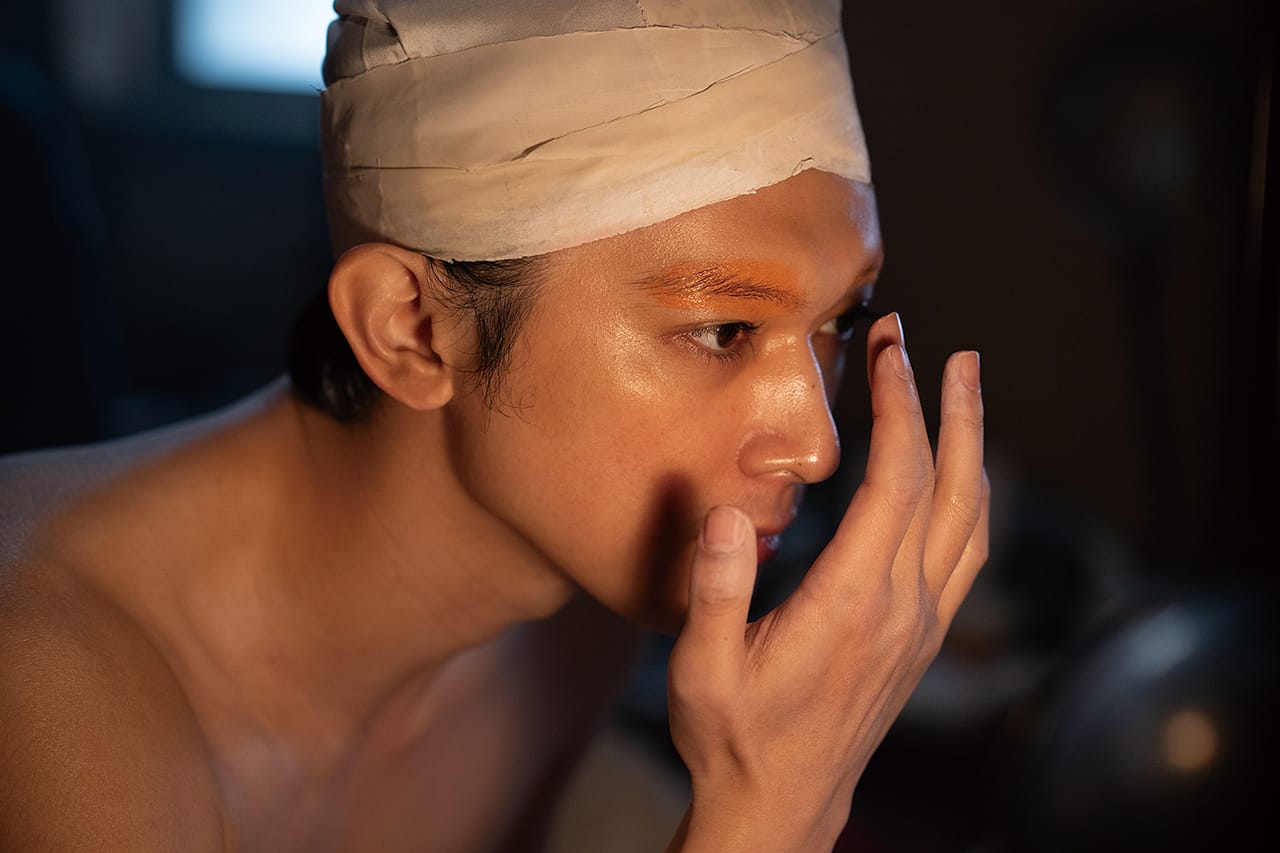

Lee Sang-il's Kokuho's is a decades spanning epic on the journey into become a ningen kokuhō (living national treasure) an elusive group artists and performers who poses a mastery of their craft. Kikuo (Ryo Yoshizawa) aspires to this within the world of Japanese's classical theatre-Kabuki as an onnagata, a male actor who plays female roles in Kabuki. Like most films about artists it draws tension from the pursuit of artistic perfection and the human connections that stand in the way of said pursuit.

Lee Sang-il's asks the viewer Why be an artist? Its hard to find any logical rebuttal. Art doesn't operate with a moral accord; it doesn't reward those who have put in the effort as a token of appreciation. Even if it did, Kikuo, son of a Yakuza member, with no blood to bind (and protect) him to Kabuki, is perhaps the one person to whom art would not reward.

Kikuo is gifted; he has a natural talent. Unlike Shunsuke (Ryusei Yokohama) Kikuo's adopted brother and later rival, Kabuki is not an heirloom that he can trace through, not something he can draw from. But he doesn't need to. His bones know the stance, the movement, the expressions, the vocals. Kikuo's devotion, willingness, and dedication to Kabuki mean that each time he is struck down, beaten, bruised, and defeated, he gets back up into position perfectly. Doesn't matter if he forgets; his bones won't.

Kikuo suffers. If you ask yourself, when does life get better for Kikuo throughout the film? It doesn't; the opening scene decades apart from the film's final is perhaps the sole moment in which Kikuo isn't suffering, that moment is violently and brutally taken from him, and he never regains it. Loss is a cyclical process continuously reinventing itself, getting closer and closer to us each time. When we aren't grieving, we are pushing others away, we are in arms with those alongside us, we are having our identity punished, and our art form is laughed at. Never a moment of respite.

But what makes the film so incredible is that while this plays in the background, and we ask ourselves "why be an artist" the film's presentation of Kabuki is so spectacular that you genuinely argue that there is something to being an artist. That despite everything logical, everything healthy, every moment of pain that you have to endure, everyone you have to push away. That there is still a reason being one.

Kikuo's adopted father and Kabuki mentor, Hanai Hanjiro II (Ken Watanabe) says that the art of Kabuki for Kikuo's is his revenge, his way of getting back at the world. The interaction is tender, but art is a language truer than words; it's hard to articulate why Kikuo chooses to be an artist. But the film doesn't need to, it shows us why. Its sequences of Kabuki are genuinely awe-inspiring; the entire film pivots on the sense of grandeur and awe generated from these sequences, and the pivot lands, the films perfection in these scenes is stunning. Kabuki operates less like a conventional theatre piece and more like an orchestra; there’s this sense of movement and energy that rises and falls, each scene is visually stunning and they are backed by an incredible orchestral soundtrack that elevates the scenes further. Ryo Yoshizawa spent over a year training in Kabuki to be able to give the performances in the film, and you can absolutely see that craft in the film.

There’s an precision to which a good performance operates, something which is negligible in terms of being able to be articulated or noticed in its absence, but it elevates and is noticeable in its presence, something that simply feels special Art is about this attainment of this sense of perfection, something so harmonious yet utterly intangible. Artists concern themselves with this because in their absence, it doesn’t exist.

It’s a selfless position to dedicate oneself to beauty since they very rarely get to witness it themselves. Kokuho doesn’t concern itself too much with the sense of perfection internally, that of the self-satisfaction of getting it right as much as it concerns itself with perfection externally, not of praise of getting it right, but of the notion of the storytelling which is delivered to the audience, and whether this storytelling is as intense, as visceral, as moving, as dramatic, as beautiful as it intends to be, if not more.

The moment in which Kikuo is able to see this beauty, finally, after everything, is such an emphatic moment.

“How beautiful”

Kokuho Trailer-NZIFF 2025

Follow our Letterboxd and Instagram to get live updates and reviews directly from our dedicated student team of film aficionados <3

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in Craccum are those of individual contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial team or the publication as a whole. While we aim to ensure accuracy and fairness, Craccum cannot guarantee the complete reliability of all information presented and assumes no liability for errors or omissions.