Waiting for Daylight

Trains, treasures, and the rivers under us.

An inevitable part of my bus commute to and from the university involves wiggling through the eyesore of construction barricades and patchworked asphalt on Wellesley Street West. We stall at the red lights and my window view is crisscrossed over by a temporary fence (how lovely). There’s a blue, cubic structure towering just on the other side. Just below its awning hangs the name of the soon-to-be train station in midtown Tāmaki Makaurau, still zip tied in a plastic sheet: Te Waihorotiu.

For over a year that blue cube incubated there, becoming something of a familiar sight while the real dynamism happens away from the fleeting attention of commuters, all the excitement contained underground. A grand opening is gently promised for 2026, and the station’s blue poutama-inspired façade – the City Rail Link brochure tells me – abstractly illustrates Ranginui’s (Sky Father) separation from Papatūānuku (Earth Mother) which ended primordial darkness in the Māori creation story. The brochure goes on to highlight the art installation suspended from the ceiling as you enter, designed to resemble the station’s namesake: the body of water under Queen Street. Yes, a stream once flowed down from the Myers Park gully into the Waitematā Harbour. Waihorotiu continues to run beneath our foot traffic today, trapped in the sewers for the last 150 years.

Waihorotiu in the pre-colonial landscape was nestled among native wetland vegetation and sprinklings of Māori pā (villages or fortified settlements), and home to the taniwha (guardian spirit) Horotiu. It was a treasured source of fresh water for drinking, also supporting ecosystems of eels, shellfish, wild and planted flora. However, European settlement in the early 1840s saw Waihorotiu forcibly transformed into a receptacle for industry waste. By 1843 it was undrinkable, had been converted into an artificial channel, and redubbed the Ligar Canal. Effectively an open sewer, it garnered complaints from residents and visitors alike for its stench and threat to public health, and was ravaged constantly by major floods. Waihorotiu was bricked over entirely in the 1870s, vanishing from the city and the landscape in our memories.

So if you happened to be one of the poor souls stuck in the city centre during the Auckland Anniversary Weekend floods of January 2023, that swift river you were surprised to find swallowing the length of Queen Street was by no means an unparalleled event.

Between buried life and lost histories, though, art and imagination surfaces as a form of remembrance and resistance.

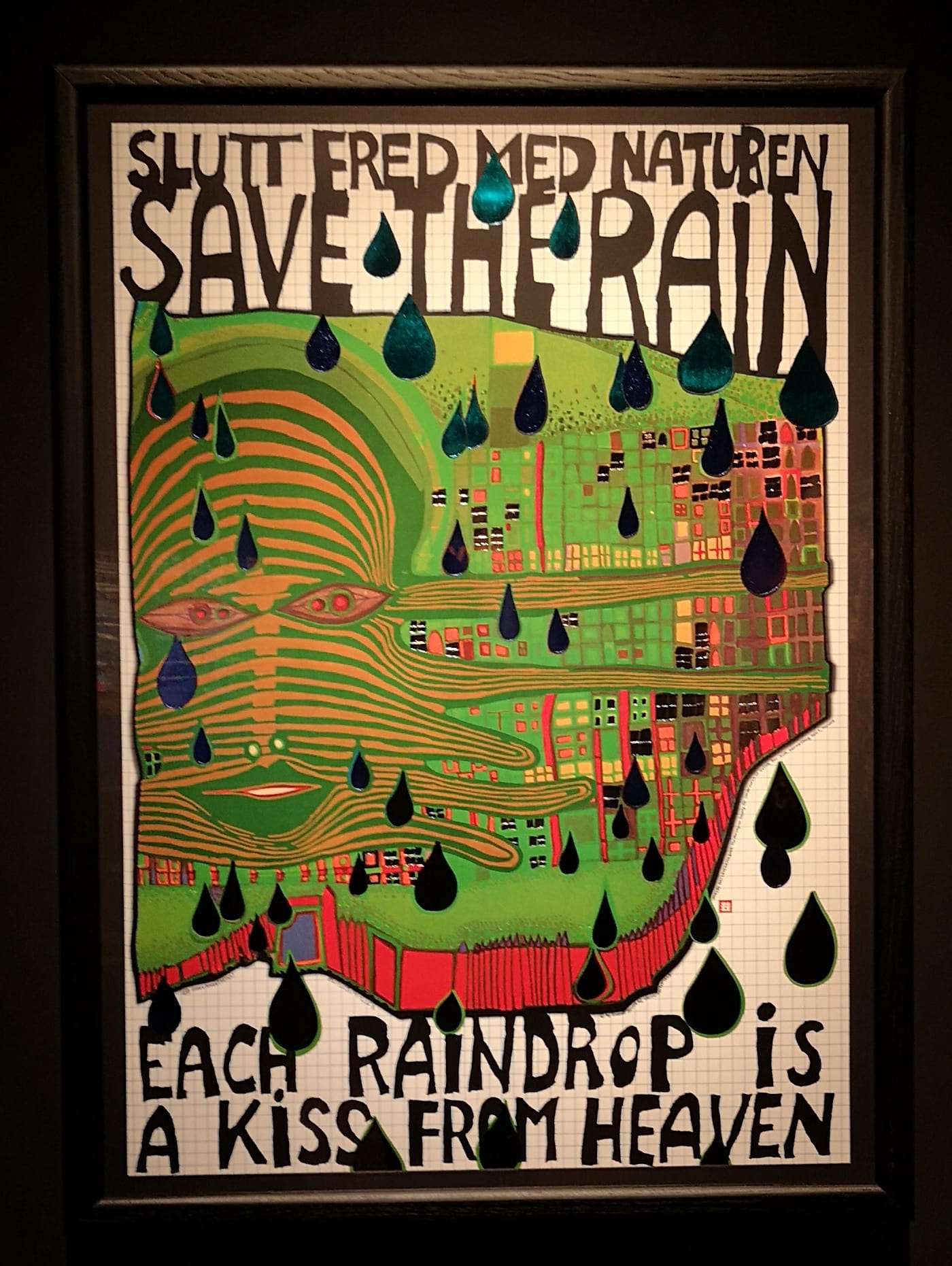

I think of Friedensreich Hundertwasser, an Austrian artist and architect who, after falling in love with New Zealand during his first visit in 1973, lived in Northland for the final three decades of his life. Besides being the designer behind the colourful public toilets in Kawakawa (a worthy stop on your next roadie, by the way), he is remembered in New Zealand for his strongly environmentalist artworks and life ethic. In his manifesto on green roofs, or “afforested roofs”, he wrote: “We must give territories back to nature which we have taken from her illegally. The nature we put on the roof is this piece of earth that we murdered by putting the house there.” When I read this at the Hundertwasser Art Centre in Whangārei, my mind flew immediately to my cosy bedroom waiting back at home. Before my wall posters and ambient lighting, which species of native shrub filled the space?

In a poem by New Zealand artist Elliot Collins, Waihorotiu is described as “river / that is covered and filled and forgotten.” That is, forgotten by humans, but not by the ancient ecosystems we are often too short-sighted to realise we belong to.

A similar sentiment lies in Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki’s Academy Award-winning film Spirited Away (2001), where one of the protagonists, a river spirit, struggles to recall his true name because his river has been filled and built over with apartments. Miyazaki’s critique of humanity’s damaged relationship with nature becomes visceral when a ‘stink spirit’ shows up later in the film, oozing sludge and everyday refuse. The creature is eventually revealed to be the spirit of a heavily polluted river – this scene was inspired by Miyazaki’s own experience of a neighbourhood river cleanup.

In 2021, Auckland-based oil painter Christopher Dews created a series of paintings which reimagine our familiar concrete-flavoured city centre into glimpses of what it could look like in the year 2050. Inside the visionary city of his artworks, Queen Street teems with green arbours and native birdsong, Aotea Square is the flourishing wetland it used to be, and Waihorotiu is restored as a shared taonga (sacred treasure) for all to live alongside. These paintings were presented to Auckland Council during a Planning Committee meeting. Today, four years on, there are still no plans to daylight the stream at the heart of our city.

Urban river daylighting has been on the rise globally, with the most successful example being the 2005 renewal of Cheonggyecheon River in Seoul. Like most urban rivers, the polluted Cheoggyecheon was concreted over and topped by an elevated motorway in the mid-20th century, creating new problems of traffic congestion and compromised air quality. The daylighting project transformed the area into a lush outdoor community space of rich biodiversity; a space to relax and breathe in. River and wetland restorations are not simply superficially attractive. They also support the infrastructural health of cities by mitigating flooding, urban heat island effects, and relieving pressure on sewage systems – a real pain point for us in Tāmaki Makaurau.

“Where the original water source at Waihorotiu provided a service to local people for cooking, cleaning, bathing and growing food… Te Waihorotiu station will soon provide the service of transport,” the City Rail Link brochure concludes proudly. For a second I want to recoil. If the entire history of our relationship with the natural world was documented on paper, would it largely be indiscernible from the transactions on a receipt? We are, perhaps, rather young and ungraceful when it comes to coexisting with our living kin: our trees, rivers, soils, the plump black eels in the Western Springs lake… I once observed them squabbling innocently over mouldy bread crusts, tossed into the water by a family in their misguided attempt to ‘connect with nature’. We are not as separated from it as we believe.

The light turns green, the bus heaves on. Suddenly comes to mind the final line in Collins’ poem.

“Water runs deep underground, / as I skim the surface”.