Wither AUSA? | Craccum Throwback

"No vote" swept the 2025 TKR AUSA elections. Turns out the same disengagement was happening back in 2015, so how did we get here? In this archival article, Bob Lack gives us the history of AUSA's decline.

Feature article written by Bob Lack, AUSA life member and member of the AUSA Advisory Board. Originally published in Issue 23, Craccum 2015. You can read every issue from 2015 now on our online archive. Note: the original article came with no supporting imagery and all have been added in this repost to contextualise and enhance the original article.

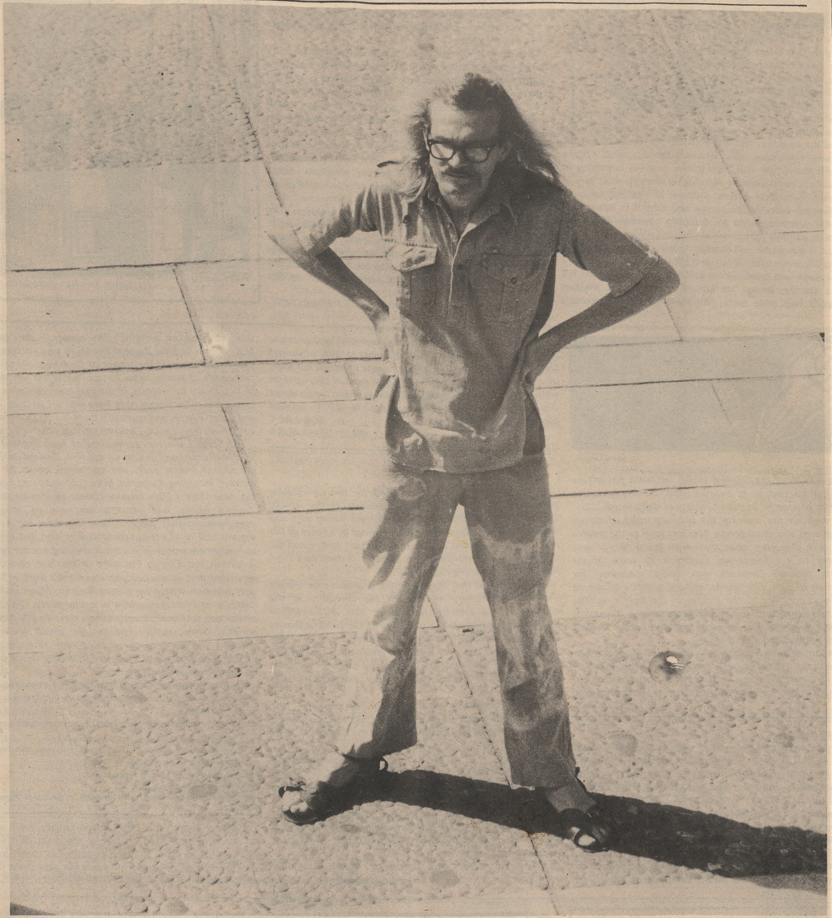

“Students vote for hemp!” — That was the NZ Herald headline sometime in 1969. It followed an AUSA Special General Meeting where upwards of 15% of the student body crammed the Student Union Quad and balconies, with some adventurous souls even on the roof[1], to debate and vote overwhelmingly in favour of marijuana legalisation.

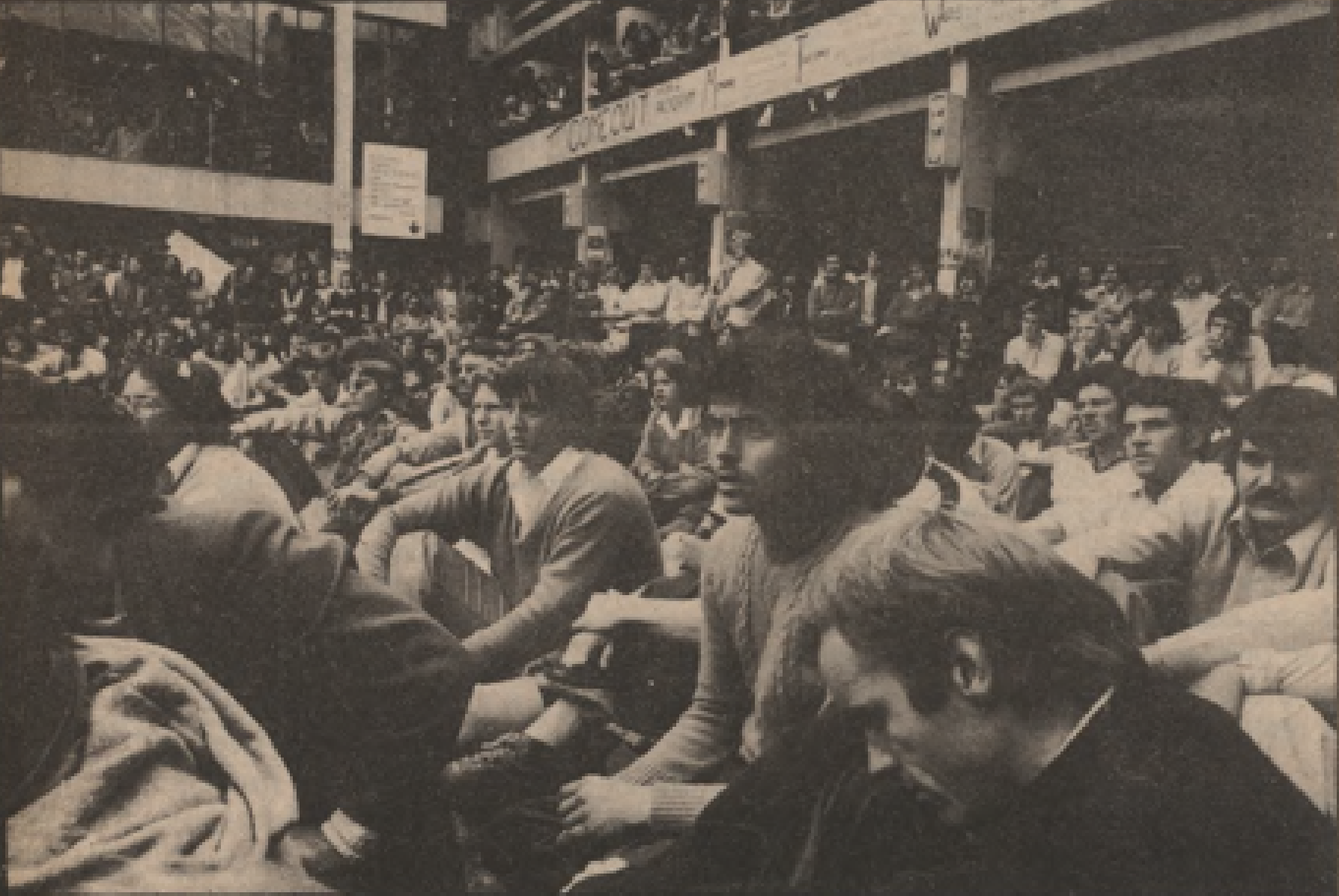

In the 1970s, we had even bigger general meetings in the Recreation Centre, and the turn-out for AUSA elections could reach about 25%; lower than the 36% of 1948, but still sufficient to provide credibility. By the mid-1990s, the election turn-out was down to around 15%, but that still represented 3,500 students.

In the recent AUSA 2016 portfolio elections, 582 students voted—well under 2% of the student body. In the less contested 2016 officer elections, 260 students voted, and at an earlier by-election just 196 students voted. A Treasurer was elected with 107 votes.

How did we get to this position, and what can we do? I think it helps to know something of the history — how the present AUSA emerged.

For its first 80 odd years the AUSA Executive worked mainly in concert with the University, fostering social, cultural and sporting activities and developing Student Union facilities — more detail in the sidebar. Then came the seminal year.

A current day health and safety officer or security guard would have conniptions. We didn't have such people, or any hi-vis vests, but nobody got hurt. ↩︎

Early History

THE COLLEGE YEARS

Auckland University College opened in 1883, as part of the University of New Zealand. In 1891, a group of students and graduates resolved to form a students’ association and to set a subscription — 2/6 a year from memory (of the minutes, not the meeting). The aim was to represent the students in all matters of interest, and to foster college cultural, sporting and social life. At that stage the association didn't run facilities like common rooms.

By 1925 there were concerns about poor college spirit and inadequate student facilities. AUCSA and the college agreed that all students would pay the AUCSA subscription of 15/- (with a joint committee able to exercise discretion, e.g. for hardship), and that AUCSA would £3,000 to building the first Student Union (the rear wing of the Clock Tower Building), with facilities such as commons rooms and a cafeteria. AUCSA members also had free membership of all college clubs, which were supported by the subscription income.

In the following decades, AUCSA focussed [sic] mainly on intra- and inter-college activities, and the AUCSA constitution reflected this. Authority resting with the Executive Committee and there were specific provisions to manage the Student Union, to control clubs and make grants to them, to manage Craccum and other publications, to run social activities, to participate in NZ University Tournaments, and to award Blues. While AUCSA had a part-time manager for much of this period, most of the work was done through specific student sub-committees.

BECOMING A UNIVERSITY

The 1959 Hughes Parry Report on university education led to the creation of independent universities and the strengthening of the academic staff and the research focus. It also persuaded government of the national benefits to flow from significantly increasing the proportion of full-time students, widening their focus from the purely vocational, and supporting them during their studies; in short creating the traditional university environment where students had time to explore, reflect and debate as well as to gain qualifications. Over the next few year,s [sic] government introduced fees bursaries, increased scholarships, and offered subsidies for the construction of student facilities; the university enhanced its student welfare services and set aside land for a new Student Union; AUSA added to its subscription a Building Levy of £1 (later £3) for the construction of the new Student Union; and AUSA restructured its Executive to create specific portfolios, including a Business Manager and a New Buildings Officer.

The new Student Union opened in 1968, paid for and furnished by AUSA, public donations and government subsidy (half of the cost up to 10 sq ft per EFTS, I think). The university paid little or nothing, though it certainly contributed management expertise and cash flow. Later the Maidment Theatre and the Recreation Centre were added (the latter designed as a multi-use facility, available for concerts, dances and student meetings as well as for sport), both part of the Student Union and both paid for mainly by AUSA and donations, plus the government subsidy; though the university did meet 10% of the theatre cost in retirn for a commitment that it could make use of some of the space.

Professional staff were employed to manage and operate these new facilities, overseen by a joint AUSA/university Student Union majority (Report of the Committee on University Government, 1972, Appendix C. The university saw SUMC as so important that the Vice-Chancellor and the Registrar were both members). This meant that the Executive and its sub-committees needed to focus less on house-keeping matters.

"ALL IN ALL, THE STUDENT UNION HAS LESS STUDENT COMMON ROOM SPACE AVAILABLE TODAY FOR 42,000 STUDENTS THAN IT HAD IN 1968 FOR ABOUT ONE-FIFTH OF THAT NUMBER."

A WIDER FOCUS

By 1968, students were funded to allow for a wider than purely vocational focus — for "conplete immersion in university life before commencing paid employment".[1] At the start of that year, the new Student Union opened, providing a marvellous focus for a full student life, and with professional staff relieving the Executive of many previous housekeeping responsibilities.

Also in 1968 student unrest swept many Western universities, sparked by uprisings in France and by opposition to the war in Vietnam. At Auckland it was agreed (peacefully) to establish staff/student consulative committees in all academic departements and faculties, and to elect studnts to Senate[2]; and subsequently to initiate or increase AUSA representation on other university bodies. In AUSA a Student Representative Council was created to provide wider student input to AUSA decisions[3]; and to provide a stronger editorial voice Craccum was made entirely independent of the Executive.

With the reduced need for Executive involvement in the Student Union management, and with the growing student interest in national and international politcal matters[4][5], AUSA started to create political and diversity positions, e.g. International Affairs Officer[6], Women's Rights Officer[7], Environmental Affairs Officer, etc. Initally outside the Executive, by the 1980s these had been bought on to the Executive, replacing some traditional roles[8] rendered superfluous by the employment of professional staff.

While interest in external politics increased, I wouldn't like to give the impression that this dominated. During this time AUSA still took many internal initatives; for example it adopted, housed and funded Radio B; started Student Job Search; started the Anti-Calendar and lecturer evaluation; and employed the first support person for disabled students. Further, it shouldn't be thought that "politics" meant necessarily left-wing; there were plenty of people from the right on the Executive during this period[9].

Report of the Committee on New Zealand Universities, 1959 (the Hughes Parry Report), quoted in Victoria University Review 1961, p. 24. ↩︎

Senate minutes 29 July 1968. ↩︎

Initally a faculty-based elected body, SRC was later opened to all AUSA members and survives today as the Student Forum.* ↩︎

Perhaps a direct result of the Hughes Parry inspired funding changes. ↩︎

An early indication of increased political awareness was a 1972 AUSA decision to devote a proportion of its subscription income to particular external causes (e.g. the Tenants' Protection Assocation and HART). This was quickly over-ruled as ultra vires. Since then many student functions have been held to raise funds for the causes of the day, but so long as universal AUSA membership continued it was accepted that subscriptions could only be spent on matters of benefit to students qua students. ↩︎

The first being the sainted Trevor Richards, first leader of HART. ↩︎

The first being Dame Susan Glazebrook, now a judge of the supreme court. ↩︎

E.g. Business Manager, House Committee Chair. ↩︎

E.g. Simon Upton PC, later a National government minister; and Peter Goodfellow, current President of the National Party. ↩︎

*Note the Student Forum has since evolved again into the Student Council as of 2019. Membership is no longer open to all AUSA members, but just the presidents of faculty clubs and associations.

THE MONETARIST REVOLUTION

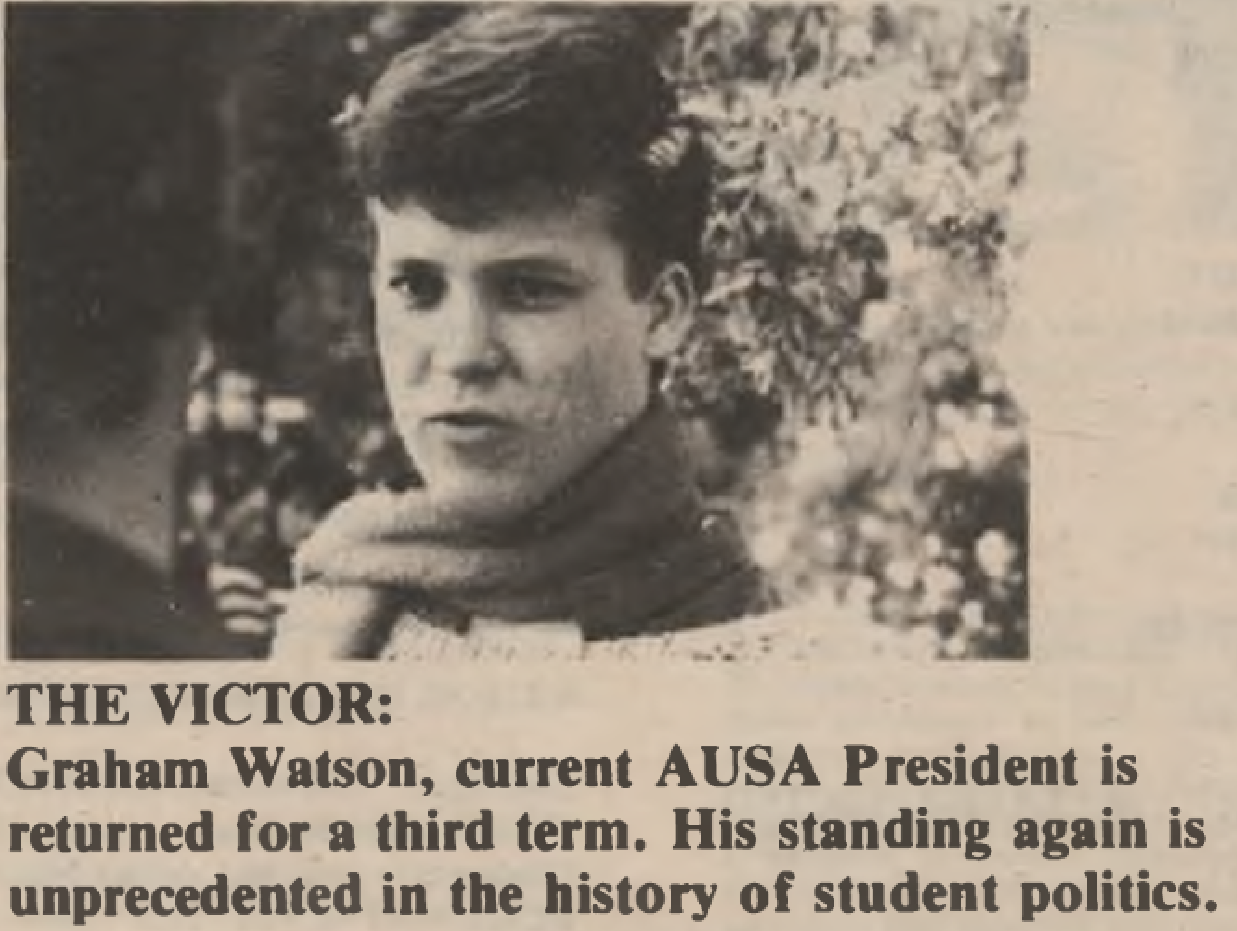

From the mid 1980's there was a backlash against AUSA political activity, led by the late Graham Watson.* He and his followers argued that the association should focus on social and welfare activities, they promoted drug and alcohol use, and they changed the constitution to have the Craccum editor elected rather than appointed on merit.

At much the same time monetarists took over the government, in the following years they made radical changes to university education. These included gutting the 1961 university acts and imposing a managerialist structure; funding research and teaching on the basis of "outputs"; dropping financial supportfor students and subsituting a loan scheme; and forcing tuition fees to rise substantially.

These changes have made a massive difference to student life. Undergraduate class sizes have increased, reducing the opportunity for discussion. With substantially increased financial pressure, many students have reverted to a vocational focus, and at least at the undergrauate level, few can afford to look beyond their enrolled courses. Many now live with their parents, out in the suburbs, and stay in their ex-school social groups rather than needing to form new relationships at university. The Student Union, once vibrant every night with student clubs and weird activities, is now dead and locked after classes.

The Student Union hasn't been significatly improved or expanded in over 30 years, and in that time the student roll has more than doubled[1]. In the original plan, more land was earmarked for Student Union expansion, but under Dr Hood, the University took that for the Kate Edger building. The University has also invaded the original union building, for example taking over the prime quad-front space for its shop and annexing the former basement coffee bar to the Maidment Theatre**. AUSA has also closed off a lot of formerly common space, e.g. for offices.

All in all the Student Union has less student common room space available today for 42,000 students than it had in 1968 for about one-fifth of that number. Furthermore, the building and its contents are generally in a very ratty condition,[2] not welcomng and not a good advertisement for the University or for AUSA. Hardly suprising, then, that the Student Union is no longer the centre of student life, or that many students never go there.

The monetarists also changed the law to force votes on universal or voluntary membership of students' associations. Despite having spent years using AUSA funds for social activities, many of Graham Watson's followers argued strongly for voluntary membership. After a lot of lobbying, in 1999 Auckland students voted very narrowly for this[3] - as far as I know the only university to do so.

I don't know this, but I imagine that the former government subsidy for Student Union construction was scrapped by the monetarists; if it wasn't then we really should raise some funds and claim more of it! ↩︎

Not ratty as in teeming with life so appearance becomes secondary, but ratty as in sad and neglected. ↩︎

With 50.2% of the votes in favour. ↩︎

*Note: Graham Watson was president of AUSA between 1985-87. He later went on to become the ACT Party Manager and was a key driver behind the introduction of Voluntary Student Membership. (Source)

**Note: The Maidment Theatre was closed and demolished in 2016. (Source)

"CLEARLY THE AUSA RULES HAVEN'T KEPT PACE WITH THE CHANGES. FAR FROM PROVIDING A STUDENT VOICE TO GUIDE THE EXECUTIVE, THE STUDENT FORUM IS ALL BUT MORIBUND, REQUIRING EXHORTATIONS AND BRIBES EVEN TO SCRAPE A BARE QUORUM."

"THE END TO UNIVERSAL MEMBERSHIP HAD A BIG IMPACT ON AUSA. INCOME DROPPED DRAMATICALLY, SERVICES HAD TO BE CURTAILED AND STAFF NUMBERS CUT."

Voluntary Membership

This isn't the place to review the whole VSM issue, but here's just one illustration of how the proponents were and are completely wrong.

At an Auckland University Council meeting in about 1997, Dr John Hood argued against universal membership. His key point was that the subscription created an unjustified obstacle to educational access, and he advanced the example of a particular single mother of limited means who was seeking to improve her lot. At the time the AUSA subscription was $139.50 a year, of which 40% went to the Building Fund, and there were discretionary provisions for those suffering hardship or having a conscientious objection. Of course AUSA was democratically run, and if sufficient students objected to the level of subscription or what it was being spent on, they could make changes; and from time to time they did. At the same time the university levied students about $60 a year for "student services" such as Student Health ($55 in 1995 — University Calendar for that year p. 92).

Subsequently Dr Hood became Vice-Chancellor, membership of AUSA became voluntary and the university enrolment process omitted the option to join AUSA (as I read it. Since section 229CA(4) was inserted into the Education Act in 2011 this had permitted the option of joining AUSA to be included in the university's enrollment process. I don't know wether AUSA and the university have since acted on this — it's a long time since I last enrolled). To meet a reduced budget AUSA had significantly to curtail its activities, then to hold up its membership numbers it decided to reduce and then eliminate subscription. The university found that it wanted many of AUSA's former activities to continue, so it had to pick up various costs; for example Blues awards, and support for disabled students.

Given that the university has less recourse to voluntary labour than the association, it's not at all surprising that Student Services Fee rose to offset any saving from the eliminated AUSA subscription. What is surprising, though, is that the Student Services Fee has now reached $738 a year — an increase of about 14% per annum compounded for the last 20 years, several times the rate of inflation*. If there is any discretion for hardship or conscientious objection this isn't obvious from the university's web site, and the students have no control over the level of this fee or how it is spent.

By definition the student body comprises all students. All that universal students' association membership did was to provided a corporate structure for the student body. At Auckland "freedom of association" has simply led to increased enrolment costs and reduced accountability to students (or in monetarist jargon "customers"). Despite this, in 2011 the ACT Party (yes, the one now led by that friendly, intelligent, understanding young chap David Seymour) persuaded the National Party to outlaw even the option of universal membership, creating the risk of a similar poor outcome at all other universities. They must be very proud.

*Note: The Student Services Fee is now $1,147.20 (Source). That is a 55% further increase over the last decade; however, there is now no longer any money left for Craccum. Since Universal Membership of AUSA was ended, the Student Services Fee has increased to 20x its initial value across the last 30 years.

Today

The end to universal membership had a big impact on AUSA. Income dropped dramatically, services had to be curtailed and staff numbers cut. The University could have used its Student Services Fee to keep AUSA in partnership, running student facilities and services. Instead, for reasons I don't understand[1], there's been 15 years of antipathy, leading to the present situation where the association is in debt, depends for a signficant part of its income on prudent investments made by former Executives, has only a terminating fixed term occupancy licence for just a portion of the buildings that its former members paid for, can't afford to maintain those facilities properly, and has insufficient staff to support the Executive. Meanwhile we have the absurd spectacle of university employees paid from the bloated Student Services Fee running such offical university events as toga parties and zombie-themed tag games[2], with professionally produced advertising and, no doubt, a good attendance of security guards.[3]

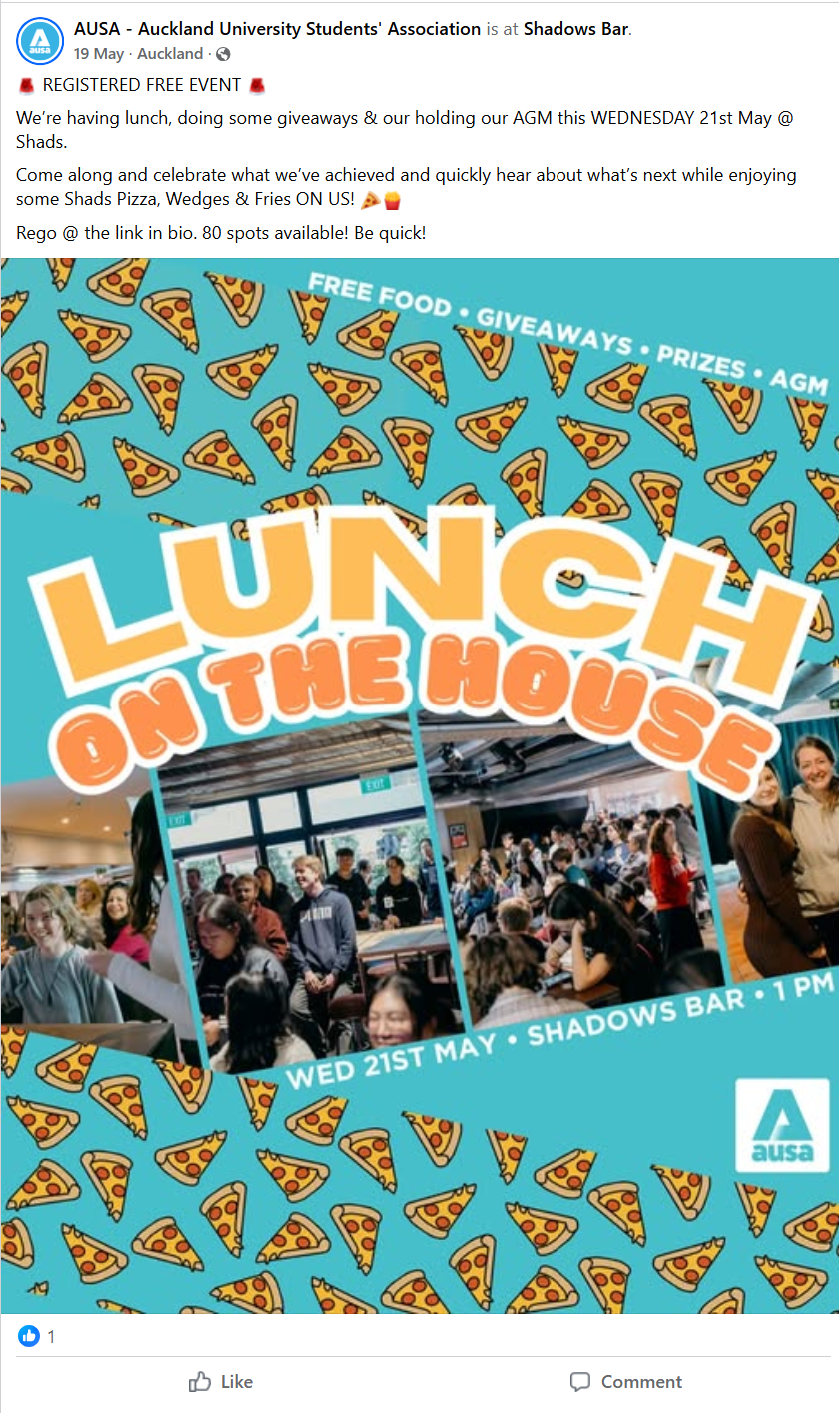

Clearly the AUSA riles haven't kept pace with the changes. Far from providing a student voice to guide the Executive, the Student Forum is all but moribund, requiring exhortations and bribes even to scrape a bare quorum. The Election Rules require candidates to participate in public meetings, which almost no one but other candidates and their close supporters attend. The Executive portfolios remain largely unchanged from the pre-monetarist and pre-VSM era, though the challenges facing AUSA today are substantially different from those 20 years ago. And, as clear evidence of just how irrelevant the average student judges AUSA to be, we have the appalling voter turnout figures outlined in the introduction. Just to rub it in, about 6 times as many students attended the University's First Year Toga Party in 2015 as voted for the 2016 AUSA president.

This isn't to say that AUSA and its officals do no good work. The advocacy services and the co-ordination of class reps seem particularly worthwhile. I admire members who join the Executive, who try to represent the students and engage with the University and government, at the same time as managing the organisation, the budget, the staff and all manner of administrative matters, and this in an environment where the law is becoming increasingly intolerant of mistakes or omissions by the leaders of organisations[4]. However, it appears that the students don't value AUSA's work, or don't understand what it does.

But which do seem to include some mismanagement on AUSA's part; how on earth do you lose money from selling beer to students? ↩︎

No insult is intended to the individual employees, who I have no reason to doubt do an excellent job within their brief. ↩︎

In hi-vis vests. ↩︎

E.g. new health & safety laws, new charity reporting standards. ↩︎

"DO STUDENTS IN FACT STILL REGARD THEMSELVES AS MEMBERS OF THE UNIVERSITY? OR HAVE THEY SIMPLY BECOME CONSUMERS, CONTENT TO ENGAGE WITH THEIR CHOSEN QUAIFCATION SUPPLIER THROUGH MARKET PROCESSES?"

On the Nature of Memories and Records

MEMORY

It's an old saw that if you can remember the sixties then you weren't there. I can and I was, but I'm increasingly unsure how reliable my memories are; of the sixties or of any period before last week.

It isn't that the memories are getting fuzzy, or hard to find. But when I've remembered a given event several times, thought about it, read about it, discussed it with other people, heard the stories; why then it becomes increasingly difficult to be certain what is a true memory and what is a later over-lay, perhaps influenced by what I wish had happened, or what someone else recalls.

In short it seems as though Dr Heisenberg has applied his most famous invention to the field of human recollection.

RECORDS

Of course when I'm uncertain of facts I turn to records. There are (or were) written records to confirm or refute many of the assertions I've made in the main article, meeting minutes, rule books, back issues of Craccum, etc. Regrettably AUSA's record systems are decaying, so the main article is based on my memories and what records I have to hand or could find quickly on line.

Decaying record systems aren't particular to AUSA; in fact I suspect there's a general principle at work - an information equivalent of the Second Law of Thermodynamics. Still, at least many of AUSA's records are written, and easy to handle. The problem will be a lot greater for future researchers, dealing with digital records. But that's a topic for another article...

THE FUTURE

Where does AUSA go next? How should it be structured for the future? If there's one thing to be learned from history, it is that the students' association changes of the 1890s, the 1920s, the 1960s, and the 1970s all stemmed from what the student body wanted.

Since the 1990s, governments have been pushing universities to increase financial efficiency and to refocus on the vocational. Rightly or wrongly, willingly or unwillingly, many students seem to accept this[1], and AUSA has been one of the casualties.

So, what does the student body want, now and into the future> I'm nowhere near close enough to provide an informed answer, but a few subsidiary questions spring to mind.

Do students still want a student-controlled central common space, such as the Student Unions used to provided? Should that be passed up for multiple student-controlled common spaces e.g. at faculty level? Or are students content to accept whatever space and facilities the University and the wider Auckland market provide?

Are students happy to be paying a compulsory Student Services Fee of well over $700, with half of this spent on "sports, recreation and cultural activities"[2], without effective student control? Should there be a board with a student majority overseeing the University's student services? If not then why not?**

Do the student representatives on university bodies function best as individuals, or would the students and the University benefit if the student body had a single mandated voice, such as AUSA formerly provided? Could the University's enrolment and student engagement processes be used to achieve this, practically and legally?

Is there a sufficent community of interest among Auckland University students for a single body to be able to represent them; or is the size and diversity now simply too great?

Some of the faculty societies seem strong. Should AUSA become a federal body, with the faculty presidents and PGSA president forming the Executive?***

Can AUSA make better use of the Internet and social media to engage with students[3] and create a shared community?[4]

Do students in fact still regard themselves as members of the University? Or have they simply become consumers, content to engage with their chosen qualification supplier through market processes?

Whatever the answer to these questions, I do hope that somebody somewhere has a plan to resurrect or demolish the Student Union. As it stands it's just an embarrassment...

*Note: Sports, recreation and cultural activities still take up approximately 1/3 of the Student Services Fee. Students in 2015 were paying for Hiwa.

**Note: Now there is the Student Consultative Group or SCG that provides feedback on the CSSF funding, but ultimately, they only consult; they don't make final decisions.

***Note: Since this article was published this has somewhat occured, with the Student Council being a collective of faculty association presidents. Although AUSA only consults with them, they are not on the Executive. Last year AUSA absorbed the PGSA (Postgraduate Students Associtation) with AUSA's new Postgraduate Education Vice-President serving as the effective President of the PGSA on the Executive.

****Note: It seems AUSA has tried to go with this idea via its plan in 2025 with the magazine becoming a hybrid publication. The jury is out as to wether Craccum online is more useful than the print issues.